Sound Observatory

On a scene in Two Years at Sea (Ben Rivers, 2011)

§ The “two years” that give the film its title not only reference a period of labour that underpins the life being lived on the margins of society but also positions certain images in relation to a sense of being castaway, separated from land or from convention. For the most part the images in the film are emphatically earthbound, consisting of various experiences of living on, from, with, even above, the land. In rural landscapes, amongst thick forested valleys, the seclusion rendered is one that is essentially landlocked. Yet the sense of being cast adrift on the seas, lost on the rotating oceans, is present too. Nonetheless, the title not only gives an oddly mercantile underpinning to the seclusion and self-reliance that the film presents (as if a last transaction granted the terms of all that follows) but also provides a metaphorical foil for the work that unfolds in front of our eyes. The specific time spent at sea—be it working on fishing boats, tanker transports, oil rigs, or even lost on a desert island, the details are immaterial—frames the ongoing, more individualistic, labour seen in the film in a particular light.

§ You propose that there is one sequence in particular that brings this connotation back—this period at sea—almost in miniature, something of a re-enactment of the preliminary labour that has given rise to what we are witnessing: a particular type of everyday life. We see a journey on foot to a further isolated spot. It takes a few minutes for the film to convey the distance travelled. Soon our protagonist, bearded and lean, reaches the unnamed, unclassified stretch of water (what Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts might label “innominate”.1 It is a grey and desolate pool of what could even be standing water, as if this were the edgelands of a wilderness, its remoteness redoubled. The figure constructs a raft using a wooden frame, an inflatable sun lounger and plastic containers. He launches himself into the centre of the loch, settling like a buoy and then settling into an image of semi-passive drifting that shines out from the film like a jewel. The camera records what is happening.

§ You realise that this a version of a Robinson Crusoe figure—Defoe’s castaway, himself a former capitalist slave trader and coloniser, here bound by terra ferma rather than uncrossable oceans. This island is encased within another, with only interior pockets of water in which Crusoe can be cut adrift once more. The isolated lake becomes our Robinson’s inland ocean, one in which it is possible for him to transport himself, without leaving, without recourse, away from the relative safety of his island.

§ The lake’s appearance suggests innumerable questions: what is the colour of this water? How deep is it at the centre or at the edge? When does it freeze? Does any sunlight reach the bottom? What life hides beneath the surface? Is it fed by a stream? Is it thick with weed or barren like a crater sealed with rain?

§ In terms of composition the shot is as simple as it could be. The camera is static. A wide angle takes in the body of water only to a limited extent, its full dimensions not given to view. It may be anticipated where the raft will drift, once it has been manoeuvred out into the middle, such that its motions are kept in view at all times. The embarkation is watched coolly, without adjustment. Amidst the stillness, all disturbances in the water seem to be excessive, even if the figure’s movements are calm and methodical. Still they are not what might be called expert. The figure is not silent. He is not a natural predator. There is a sense that he is determinedly stepping into a medium that is not his own. Clearly this is an excursion into unusual territory; it is an extraterritorial gesture. The scene is photographed laterally, as it were, emphasising movement from side to side, in fact from left to right, as if encoded according to a Westerly drift. The flat silver basin is punctured as the raft proceeds toward the centre, achieving a certain degree of independence from the shore before the figure gently changes position, bringing his legs out from under him and leaning his upper body forward slightly. His final position is that of a man who has just sat up in bed, fresh from a dream.

§ You note that there would be a notable difference between the upright rafter, standing balanced with his stack of provisions, using a long oar to punt his way down the delta to the open sea, and one in a more lateral orientation—the figure lying prone—as if this position held some other significance. You have seen it elsewhere in the film too: our hero hermit clearing the clutter from a caravan bed in order to sleep in the middle of the day, photographed through dirtied glass as if to meld his features with the surrounding trees. Another scene sees his remote walk interrupted by another nap, the bearded figure suddenly lying supine in the heather. Is this the intermittent assumption of passivity? A purely practical necessity? And when later, on the makeshift raft, the figure is bent at the waist, perhaps this suggests that his passivity is now poised, as if his waiting is not that of the resting traveller or the man of leisure but the stance of one who tries to occupy territory between sleep and wakefulness. Adrift on the lake, the figure is awake and restful in the same moment. These are instances of taking pause, it seems, a process of positioning oneself outside the reach of one’s surroundings. Switched off, stepped out. A desert father cutting ties as he disappears into the shadowy sands.

§ The act of fishing seems incidental here, the line trailed into the water on one side of the craft more like a token anchor than a device for hunting. This slightest of filaments keeps this satellite from careening fully out of orbit, as its pilot risks being abandoned completely to the cycles of gravity that cushion the earth. This may be, in some way, what the film is about: orbiting states of proximity and the distances between one set of values and another.

§ Our near mute protagonist is Jake Williams, the isolated location Aberdeenshire in north east Scotland. It is filmed by Ben Rivers in 16mm, on five separate trips accompanied only by sound recordist Chew-Li Shewring. Each visit lasts between one and three weeks. The film rotates through the seasons, the production schedule adapting to changing conditions. Although there is no script, there is a list of possible actions and agreed-upon activities. This is Rivers’ first feature-length production. It returns to a subject he has filmed once before, in 2006, for the 14-minute film, This is My Land, in which Jake is seen in a similar scenario. The older film also has a title with a possessive emphasis, indicating perhaps that territorial boundaries and private ownership are the precursors for any consolidated individualism or alternative way of living. Whereas the tone was lighter in the previous film, with sequences more fragmented and speaking voices heard, now Jake is reticent and the shots are slow moving. Time is approached very differently. Any obvious anachronism in the “mythic time” being conveyed is effectively flattened and homogenised by the monochrome aesthetic.2 Rivers himself strives for settings that are, in his words, “undefinable in time”, and the use of black and white stock edges it further away from documentary, perhaps nearer to an avant-garde heritage.3 This is not ethnographic film-making, observing and recording a human subject; nor is this reportage. Our actor is not following direction. Yet his behaviour is clearly not unaltered. Scenes are the product of a collaboration that is not given, a mixture of genuine habit, plausible fantasy and a banal yet cinematic surrealism. There are levels of construction here that allow aspects of fiction to bleed into any seemingly standardised document of portraiture.

§ Much of Jake’s represented world is analogue, filled with an accumulated clutter of old cassette and record players, pen and paper. The presence of the hand is evident throughout. The filmstock is processed by hand too; inconsistent waves and blushes flare on screen, as if chemical signatures wafted across the images from time to time. We are connected here to the moisture of the eye, reminded of the transience of celluloid. As well as implanting texture to the images, there is an added emphasis on the physicality of the life we are watching: tasks that are common yet here seem to be elemental, hard fought. This is film-making that is hands-on yet intuitive, building up a composition of images and sounds as if physically constructing an object. From the build up of interconnected layers and represented depths, a cumulative language of “gestures and movements” seeks to occupy space in different ways.4

§ You then ask yourself, associations with Robinson Crusoe aside, what kind of solitude is being presented here? Certainly there is an emphasis on living with different forces—natural rhythms, weather conditions, fluctuating resources and so on—and this forms a kind of game of resistance and complicity that requires improvisation and adaptation, “intelligence, self-interest, prudence [and] foresight”.5 Yet rather than solitude it seems more like what Roland Barthes calls, in his 1977 lecture series on ‘How to Live Together’, a form of anachoresis, a ‘retreat’ that he describes as an “act or state, or concept [...] of separation from the world that’s effected by going back up to some isolated, private, secret, distant place.”6 Given that evidence of some low-level engagement with a wider community, no matter far off-grid he might be, we might say that this is what is being enacted in the walk to the fishing lake: an enfolded quality of separateness that exists within an already withdrawn mode of living. It is the image of an inner retreat within an outer one.

§ Barthes clarifies that anachoresis is “not a matter of absolute solitude, but rather of this: a way of reducing one’s contact with the world + individualism (individualistic asceticism)”.7 The latter is symbolised throughout the film in countless ways: evidence of character not only in physical appearance and the movements of Jake when on screen, but also the world of objects and spaces that he has surrounded himself with, and which we (as the watching camera) become part of. This kind of individualism is evidenced in a prosaic inventiveness, a personalised adjustment of the smallest details of existence such that they can then take on the unique colour of an independent life. If a retreat is sought when fleeing the state, the taxman or the army, whether or not it has to be earned by two years spent at sea, what the film shows is a phase of manual labour that comes after, one that might be closer in form and function to prayer, or even subjective activism. As Barthes suggests, this kind of retreat often constitutes an “individual’s solution to the crisis of power”, formulated as the precisely rendered objection or rejection to such power.8

§ You start to ask questions concerning the film’s relationship with sound or with field recording. You see that Chu-Li Shewring, the film’s sound recordist, is herself an artist and film director, often working in collaboration with Adam Gatch, Jeremy Deller and Patrick Keiller (a filmmaker with his own Robinson complex). Much of her other work evidences a similar tactic of forcing alignments and disjunctions between image and sound, often undermining and emphasising visual gestures with an auditory slapstick.9 As with various examples of this effect in other films, the composite sound design in Two Years at Sea is for the most part dominated by non-diegetic sound, where the source is not visible on screen and often not even implied by the action. Whilst the most common instance of this method—i.e. the voiceover—is something that Rivers uses often, this is here entirely absent. No accompanying testimony explains the imagery or links up the edit. Yet the definition of this type of non-diegetic sound is not quite straightforward. The film accumulates a presence of sound that can certainly be indirectly associated with the images that are seen on screen, even the world that is being represented. Yet the emphasis of these sounds is often slightly shifted; for example, postponed until a previously separated sound / image coupling are reunited, or where certain sounds are recorded from close proximity, therefore transformed from what might be considered more naturalistic forms of recording. The isolation of the sounds—say from a crackling fire, or snowfall in a forest—forces them to be more prominent that they might otherwise be. The concentration of the sound world we are presented with is inconsistent—it may seem naturalistic, as if we ourselves are there, listening in, yet the central point of this audibility shifts around the imagery as much as the edit chops and changes. Our attention, or our attentive listening is moved around the ‘space’ of the film like a piece on a game-board. Just how the coherent sound-world of the final mix is alien to the world we enter visually, may depend on our understanding of listening. What is it that could come from outside the ‘space’ of such a given environment, as we watch one image fold into another, two sounds overlaid, then a sequence where nothing seems to move or resound, and it is seems as though we are simply looking through a window?

§ If there is a tendency toward transparency in field recording, where sound might be let through without additional interference, then what would a technique of transposition—wherein ‘naturalistic’ recordings are played back separate from the images they link with, or where they precede or retrieve their visual counterparts—do to the transparency of the scenario being depicted? Of course, it is worth pointing out in relation to the technical methods being used, that more often than not audio is not being captured on the film camera. A 16mm Bolex camera does not bind image and sound together within the material apparatus of the device. The two need to be synced together subsequently (i.e. in the edit) for the ‘normal’ construct of sound and image to subsist. It is strange to think of this conjoined structure in terms of transparency—if we transpose the term from our comment on field recording—yet it may be helpful in allowing us to see how a certain sequence within a film, i.e. one where there is seemingly no interference with the image/sound coupling, may come across with more clarity or take on another significance.

§ In his Notes on Cinematography, Robert Bresson suggests that “one can not be at the same time all eye and all ear”, stressing that sound and image in cinema have the capacity to cancel each other out, when they should be put to work in a “sort of relay”.10 Bresson pitches eye and ear together as the malleable components to be used in different compositional structures in film. Where he claims that the “eye solicited alone makes the ear impatient, the ear solicited alone, makes the eye impatient”, Bresson urges the filmmaker to “use these impatiences.”11 But it is a process of “governable” modulation for the viewer too, and one that might be thought in terms of a kind of ‘floatation’ over and above shifting binary oppositions. All of this seems directly appropriate to the lake scene in Two Years at Sea.

[...] [silence, not silent, quiet elongated, un-cut]

Bresson gives a maxim: “Against the tactics of speed, of noise, set tactics of slowness, of silence.”12 It is perhaps these contingencies, imbalances between what is slow and what is fast, what is full of noise and what silent, that takes on added import for the castaway. Defoe himself asks, in a footnote ruminating on the speed of sound, in relation to Crusoe hearing cannon shot from a far off ship, “[d]oes sound move in a right line the nearest way, or does it sweep along the earth’s surface?” before himself giving an answer, saying that it “moves in the nearest way; and the velocity appears to be the same in the acclivities as in declivities.”13 Yet this assurance of clarity in the transport of sound does not seem to reassure us totally. Back at the lake, as we watch the raft occupy the disc of water like a floating fort on a sliver of mercury, we are left with time to speculate on the angle of the mic boom, the distance of the recording device from the shore, the thickness of a blimp against the wind, the polarities of the microphones. In the limpid transparency of the image, with its indexical traceable sound world, its meditative POV, we begin to ask to what degree such contingencies locate and emphasise certain details above others, the orders of dependency between image and sound, between one sound and another, let alone how such recordings might be combined in the image/sound mix.

§ The vulnerability of the makeshift raft, even on this mirror-like water, cannot help but make you think of the Dutch-American artist Bas Jan Ader, setting off across the Atlantic in his tiny one-man boat. There is no sense of crossing here, no traversal that need be accomplished, or valorised as the attainment of the ‘miraculous’.14 If the act of fishing has become incidental, there is a sense that the detachment from the land is something more akin to a ‘circling’, something more to do with magnetic fields, a combination of resistance and attraction, the raft floating close to a central point only briefly, before drifting inevitably to the edge. It may be blown by winds but may also follow a radiating energy that is distributed between the mass of water and the land it covers. Witnesses to this slow moving centrifugal force, we watch the needle move outward, a long player revolving with the planet, as the free floating space capsule moves toward the bank. There is in this scene a sense of resumption—of there being a plane upon which the gravitational slump would come to rest. But actually it is this assumption that is undermined, as the sought after balance point is itself subject to axial forces, sliding the craft away from equilibrium.

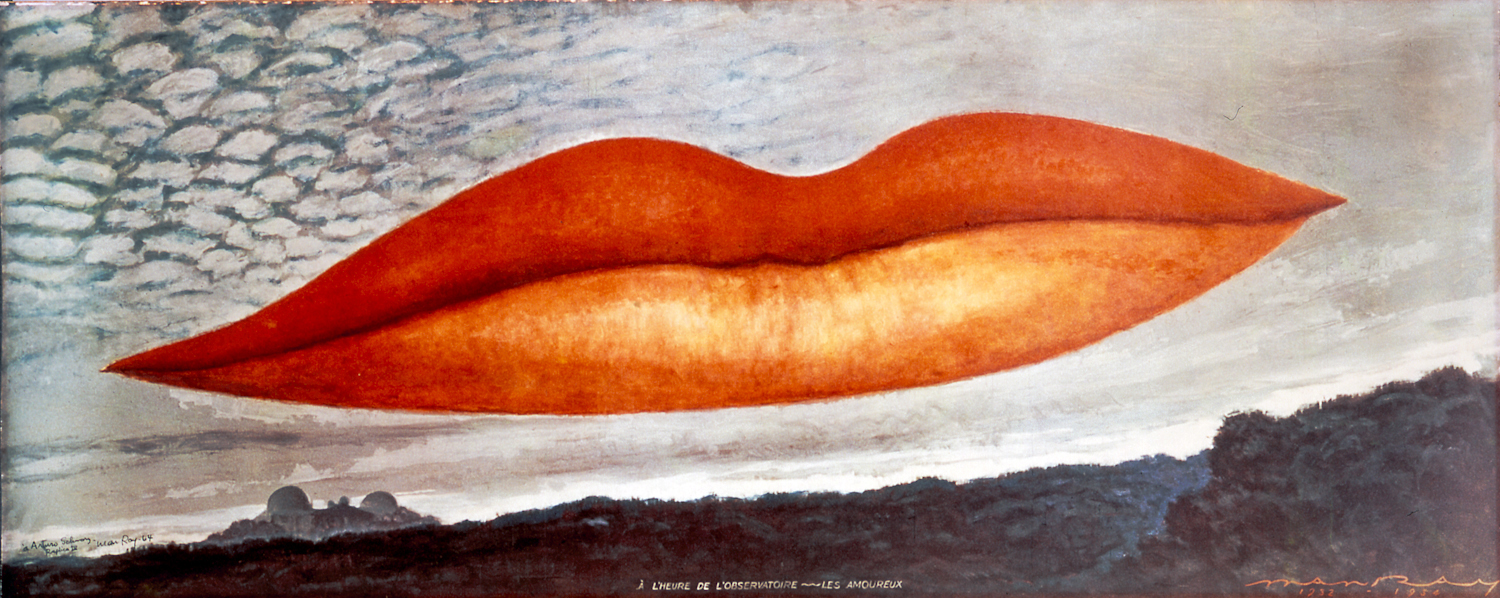

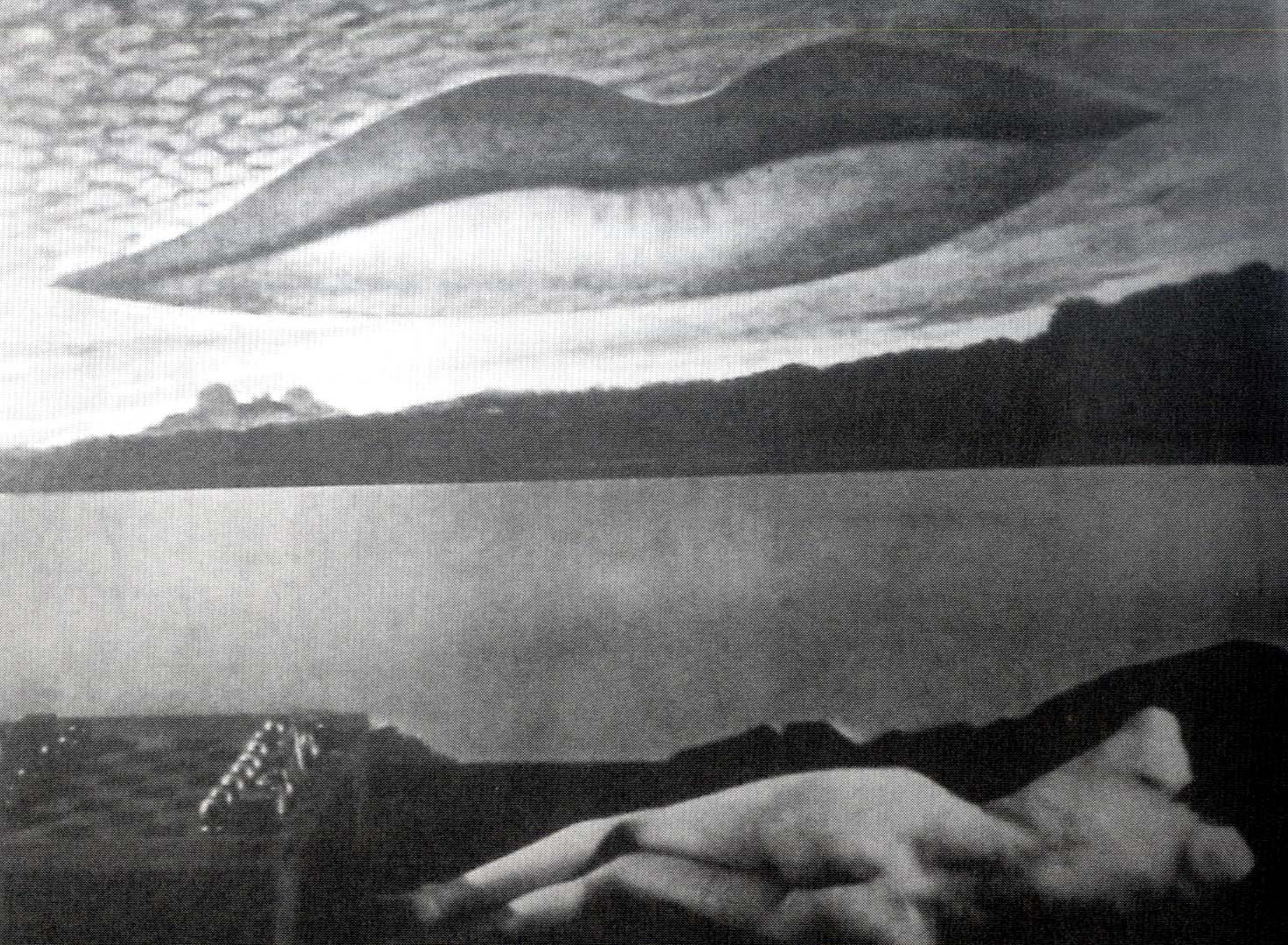

§ You wonder what could be made of similarities between the way the lake scene is composed—specifically in relation to an earlier shot taken from the window of Jake’s cabin, with staggered tree-lines in the distance, looped by low cloud—where the landscape takes on something of the anthropomorphic imagery of Man Ray’s surrealism. You think particularly of his 1934 painting entitled Observatory Time (The Lovers), a tribute to his former lover Lee Miller. The elongated lips of Miller’s mouth, pursed together, float above the tilted landscape, the bundled domes of an observatory building at the lower left of the canvas, echoing Jakes belongings piled at the side of the water. But there are other references to painting too. In the montage documenting Jake’s approach to the lake, there are repeated shots of him carrying his equipment, with floatation devices slung around his waist and the wooden frame balanced on his head. Not only is this reminiscent of the dexterous efficiency displayed by people travelling long distances to find water, there is something anachronistic about his gait and appearance, particularly the close-fitting hood. He becomes something of a figure from the middle ages, or the early Renaissance, to be found in Breughel’s winter landscapes or a wayfarer imagined by Bosch. Worldly attachments are strapped to his body, reduced by experience and utility. The determined pedlar becomes the itinerant wanderer of Romantic legend. Yet there is also something routine about his procession, as if this were a regular journey that took in certain territories according to a specific schedule. The task may be nothing out of the ordinary. The way the journey is compiled, with multiple shots of the lone figure traversing the landscape from one edge of frame to the other, ties in with Rivers’ stated admiration for Bruce Baillie’s Mr Hayashi (1961), a three-minute portrait of an individual punctuated by rhythmic traversals of the framed landscape.15 In both films, as well as shots of a walking figure being followed (or ‘pulled’ toward the camera) at close quarters, the edit is often dictated by the time it takes the subject to walk from one side of the image to the other. This gives such a predictable structure to each sequence that the viewer becomes overly sensitive to any deviation from such manifest timings—an example being when Rivers does not cut when Jake’s raft touches the side of the lake but waits until he pushes off once again, back out into the wilderness.

§ Origin of the Species from 2008 is again shot through the seasons, this time in the “garden of S., who lives in the wilderness and builds contraptions”; the ingenuity and work ethic that occupies the centre of Philip Trevelyan’s The Moon and the Sledgehammer (1970). Improvised camera angles, using tractors as cranes, using only natural light; where the camera became part of the furniture (yet at the same time the filming became the main event in that closed community). Exploration into the nature of the world; the enthused and awed thoughts about Darwin and evolution providing an odd counterpoint to the creationist thoughts gently expressed by one of the sons in The Moon... The comparisons with that film are subtle but consistent, not only with the general air of work, idiosyncratic labour directed at odd inventions, large-scale contraptions and potentially aimless constructions—a metal boat in one, a Heath Robinson pulley system in the other—but also the elaborate use of a circular saw, power units somehow rigged up in clearings, interiors being swamped by no other concern than for the ongoing (and endlessly deferred) practical task. Against the morphogenesis, the impossibility of nothingness becoming the world, there is stacked the solution of time. Voiceover that occur over the telephone, then in clearer audio. Taking in references to Darwin and quantum physics, these are still gestures of survival.

§ As well as a hopeful pessimism about the present and a taste for visionary post-apocalyptic wreckage, a key theme in Rivers’ film work is the importance of written (and spoken) text and the cinematic presence of the book. Almost all take a text as their starting point. Two Years at Sea is partly based on a reading of Knut Hamsun’s Pan, a symbolic novel that begins with an individual living alone in a forest hut, leading to Rivers’ short-lived desire to locate and film a hermit in Norway. More general influences might come from the writings of J. G. Ballard or even Russell Hoban, and combine with utopian/dystopian fiction, building up into the necessary features of individual films. The 2015 work, There is a Happy Land Far Awaay, takes as its foundational text a prose poem by Henri Michaux: ‘Je vous ecris d’un pays lointain’ [‘I am writing to you from a distant country’]. Rivers’ film is constructed from footage of the remote sub-tropical island of Vanuatu in the South Pacific, subsequently devastated by Cyclone Pam in March 2015. Michaux’s poem is an epistolary account of a strange otherworldly place, detailed a surreal description of somewhere absolutely other but which could also be a familiar world made strange. The text—one of what Paul Auster calls Michaux’s “imaginary anthropologies”—contains a plaintive emphasis on sound.16 In one section, the female narrator relates that: “At night the cattle make a great bellowing, long and flutelike at the end. We feel compassionate, but what can we do?”17 This uncertainty is embraced in Rivers’ film, the voiceover repeatedly rehearsed by an awkward female voice, the final recording including hesitations, repetitions, bursts of laughter and interjections from the director. The additions bring another layer of complexity to an account of already irretrievable distance. It suggests that the voyage to this distant land continues, even when images of the fabled destination are before us. We are presented with a composite impression of the island, with stretches of jungle and active volcanoes—their deafening eruptions often making the voiceover inaudible. There are landscapes of ash, submerged wartime vehicles, half-wild piglets feeding in the mud. The result is somehow apocalyptic and idyllic. We watch a small group of children stroll across the shallows of a river delta, which widens out behind them until it meets the sea in the distance. The viewer might be convinced that these youngsters are crossing near the very edge of the (flat) earth, warily at ease with the end of the world just over their shoulders. As well as the opening sequences of Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998) in which American soldiers wander in philosophical unease amongst island tribes before battle, there are echoes here of Werner Herzog’s La Soufrière—Warten auf eine unausweichliche Katastrophe [‘La Soufrière—Waiting for an Inevitable Disaster’] (1977), based on the impending volcanic eruption on the island of Guadeloupe. The three outliers that Herzog encounters, each with their own reasons for not evacuating the island, seem like similarly incongruous yet powerfully symbolic inhabitants of a place very much out of kilter with regular expectations of space and time.

§ In Rivers’ 2008 film, Ah Liberty!, the soundtrack is again, for John Hutchinson, “illogical [...] combining unsynchronised voiceover with unexpected moments of silence, hints of equipment noise, and oddly inappropriate fragments of music borrowed from old movies.”18 It may be that the film’s title is a quotation from Robert Pinget’s 1958 novel, Baga, a satirical story about a laughably disengaged King drifting through his duties, doing little but eating, sleeping and watering his plant, propped up and misdirected by his Prime Minister, Baga. After sleepwalking into war, the King retreats into solitude and senility in the woods before eventually returning to the throne as if nothing had happened. Early on the King exclaims: “Ah, Liberty! Liberty is the absence of ideas. That’s what I like best.”19 Again it may be that the appeal to an ‘unthinking’ mode of existence—which is to say a somehow innocent, quiet, non-destructive or conniving life—is what Rivers has recognised. The King elaborates further on his liberty: “I have fallen back on the things I used to like, which are not ideas. And I cultivate them. They are feelings. Or rather, impressions. The impression of well-being. The impression of understanding. That’s the real life.”20 It may also be that this corresponds with Rivers’ own method, particularly when generating combinations of sound and image. In an interview with Frances Morgan, Rivers suggests that, for him, sound “comes together after a process of playing with the material, often trying sounds which may be in disjunction with an image, following uncertain feelings which can be tried out quickly with Final Cut Pro.”21 This seems pleasingly similar to the quiet (yet mad!) King’s liberty, away from the role for which he is irretrievably ill-suited—an appeal to ‘uncertain feelings’ as a form of understanding, however fleeting it may be.

§ Ah, Liberty!, Rivers’ own document of this kind of understanding sees a group of masked children playing with abandon in an undesignated time and location, perhaps in the edgelands of an undisclosed civilisation. Again we could be watching ancient hinterland dwellers or the survivors of an apocalypse. Yet theirs is an isolation without loneliness. A small community exists (arguably closer to Barthes’ vision of a small, idiorhythmic group), living close to animals— lizards, dogs and horses—and half-forgotten machinery piled up in technology graveyards. This is an existence that has reset, finding its own way forward with available resources, without reference to broader social or political conventions. It is shot in myth-making sepia, the imagery and sound tending towards the primal and the primeval as well as the romantically idyllic. Bordering landscapes are shown to be large-scale, near sublime, defining the limits of this self-contained world, hemming it in with stretches of water and forest. The masked imps may well be to nature but their world is also cartoon-like and potentially savage. The film echoes Two Years at Sea at various points, with some shots appearing as if exactly replicated. Again the seasons are accounted for. Sloping rain falls against banded landscapes, watery expanses clipped by forest verticals. There is a hint of pareidolia, seeing faces in passing clouds; the image of fire becomes emblematic, as does its magnified audio. There are shots of a baby lying prone in amongst stones, another passive assumption of liberty.

§ There are associated similarities between Two Years at Sea and Lisandro Alonso’s La Libertad (2001), another film said to be an influence on Rivers’ work. Alonso’s film shares the same affectionate focus on the passage of time, particularly spent at work, with daylight hours filled with tasks, a sense of forward motion, of need and necessity. Much like Two Years at Sea, the final scene sees the silent protagonist—a woodcutter whom we have followed stoically through his daily routine—sits by the fireside, an electrical storm gathering in the background. Instead of a drawn out fade to blackness and silence as Jake’s fire turns to embers, here a thunderclap and the first fizz of rain accompanies an instant cut, followed by the film’s title emblazoned like a descriptor of the day-in-the-life that has just been witnessed. These final sequences both use the cliché of recorded fire, with its recognisable close-mic-ed intricacies. Yet the insistence of both film-makers seems to rescue it from being clumsy. The wordless face of Jake passes through a complex range of expressions, from introspection, maudlin recognition of the camera, calm contentment, distracted reveries, and so on. The sound of the fire seeps like an inconsistent rhythm underneath, for you reminiscent of the sound of a group of turnstones feeding on a shingle beach, their adept rotating of pebbles forming a delicate fizz that can be heard clearly over the rotary waves behind. The slow fade of this last scene in Two Years at Sea stands in contrast to the scene at the lake. The finale is darkly enclosed and intimate, whereas the lake is brightly exposed and open. You think of another line from Pinget’s novel, where the semi-reclusive King is contemplating music that is being played in the forest: “The forest should amplify the sound, but in fact it muffles it. At first one finds this music sad. But not afterwards. It no longer expresses anything. It’s like the sound of a faint wind, its lamentation forgotten, or stones in the mountain.”22

§ Slow Action (2011), the film Rivers completed just prior to Two Years at Sea, departed from his habit of using location sound that has been specifically recorded. Instead he used sonic reference points from existing cinema, all music being lifted from existing films, mostly science fiction movies from the 1970s. The film consists of four fictionalised accounts of islands, bringing together footage from real locations with voiceover composed by science-fiction writer Mark von Schlegell. The text details the nature of these symbolic islands, curating them as entries in what von Schlegell calls The New Earth Encyclopaedia of Preserved Utopias, making reference to all manner of literary antecedents from Herman Melville, Jonathan Swift, Jules Verne and Samuel Butler.23 Again there is a deliberate and carefully modulated disjunction between what is seen and what is heard: combinations of voice, sound, image and movement that have no doubt emerged in the editing suite, rather than being defined in advance. The consistent appeal to founding texts is satirised in the final section, which details the civilization of ‘Somerset’, an island that Rivers invented and conveyed through footage constructed in his home county of the same name. The voiceover claims that certain sects in ‘Somerset’ were founded from four seminal publications—Leon Trotsky’s The Permanent Revolution (1931), Jean- Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions (1782), Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and Zitsko’s No Frontier—with each book washed up on the shore, found inside a trunk with a newborn baby. Of course the latter is an invention, von Schlegell describing it as being “now lost to Somerset”, as if emphasising that even fictional foundations are subject to entropy and loss.24

The image and act of reading has significance in many of Rivers’ films, as well as being prominent in the work of his influences. Jake is seen poring over books inside his home or reading in the sun-filled yard. The painter Rose Wylie reads aloud n Rivers’ most recent filmic portrait, What Means Something (2015), included in ‘Earth Needs More Magicians’, an exhibition at Camden Arts Centre. It is possible to link this with image from Margaret Tait’s 1952 Portrait of Ga, a four-minute account of her elderly mother living alone in the Shetland Islands. Again the protagonist is shown reading from a book, held open on the lap, its pages edged in red, with the words just visible on the screen:

Chapter 1

A Theory

Once more this suggests something powerful in relation to what Rivers’ seeks to extract from literary texts in his film works: an appeal to theoretical material (the ideas rejected by Baga’s King) through the gritty, lived-in, labour in the practice of everyday life. This is the impact of literary culture, how it may provide the preliminary labour (‘at sea’!) of instructions as to how to live, how to survive, in the face of increasing pressure from civilisation at large.

§ As a final thought, you go back to Baga, recalling that the King, toward the end of the novel, had started to build a raft, hoping to escape his office. He is forever finding fault with it, developing a paranoid mistrust of his materials, before the impulse to escape is forgotten and the raft never mentioned again. You also think once more about the raft seen on the lake, trying to imagine it as a sonic phenomenon of some kind: the concavity of the land pointing skyward, Jake skating on top of a speaker cone. You see his faint fishing line as just another part of his function as a stethoscope on the live surface of the water. Rivers describes his films as propositions, yet you find it difficult to proposing any concrete commentary on the sound of this scene in isolation from all tht surrounds it or how it relates to the entirety of the film. You quote the King once more, as you speculate as to the specific qualities of his speaking voice, even as you ‘hear’ it inside your head as you read: “But it’s difficult to talk about sounds.”25

Notes

1 Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, Edgelands, 2011, London: Jonathan Cape, 72.

2 Andréa Picard, ‘A Man Apart’, Sight and Sound, May 2012, 24.

3 Frances Morgan, ‘Sound on Film: Listening to Ben Rivers’ Slow Action’, np. <http://www.soundandmusic.org/features/sound-film/listening-ben-rivers-slow-action>

4 Picard 2012, 24.

5 Roland Barthes, How To Live Together, Session of January 19th 1977, 14-15.

6 Ibid. [Barthes, Session of January 26th 1977, 24]

7 Ibid. [Barthes 25]

8 Ibid. [Barthes 24]

9 Cf. Mantis Tales.

10 Robert Bresson, Notes on Cinematography, trans. Jonathan Griffin, New York: Urizen Books, 1977, 62.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., 63.

13 Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe: The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner who Lived Eight-and-twenty Years All-alone in an Uninhabited Island on the Coast of America. J. Gold & J. Mawman, 1815, 160.

14 Something about Bas Jan Ader and the surrealist ‘marvellous’...

15 Baillie [http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xqltf_mr-hayashi_creation]

16 Paul Auster and J. M. Coetzee, Here and Now, 2015, London: Vintage, 215.

17 Henri Michaux, ‘I am Writing to you from a Distant Country’ in The Swanee Review, Vol. 57, No. 4 (Autumn 1949), Johns Hopkins Press, pp660-664.

18 John Hutchinson (2013) Ah, Liberty! Dublin: Douglas Hyde Gallery, np.

19 Robert Pinget, Baga, 1967, London: Calder & Boyars, 6.

20 Ibid.

21 Morgan, np. [My emphasis]

22 Pinget, 63.

23 Frieze, Issue 141, September 2011, 140-145. The three islands upon which much of the film is based are Lanzarote, Gunkanjima and Tuvalu.

24 Ibid.

25 Pinget, 63.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YHNfaMxTSg]

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwGNAIbe-xQ]

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6-8Qn8YQN8]

The Hyrcynium Wood (2005) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Gs5M92-rts

House (2006) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkQjOhzDSRY

Ah Liberty! (anamorphic 16mm film with sound, 19 mins)

There is a Happy Land Far Awaay (digitised 16mm film with sound, 20 mins)

Origin of the Species (16mm, 16min, colour, 2008)

§ You propose that there is one sequence in particular that brings this connotation back—this period at sea—almost in miniature, something of a re-enactment of the preliminary labour that has given rise to what we are witnessing: a particular type of everyday life. We see a journey on foot to a further isolated spot. It takes a few minutes for the film to convey the distance travelled. Soon our protagonist, bearded and lean, reaches the unnamed, unclassified stretch of water (what Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts might label “innominate”.1 It is a grey and desolate pool of what could even be standing water, as if this were the edgelands of a wilderness, its remoteness redoubled. The figure constructs a raft using a wooden frame, an inflatable sun lounger and plastic containers. He launches himself into the centre of the loch, settling like a buoy and then settling into an image of semi-passive drifting that shines out from the film like a jewel. The camera records what is happening.

§ You realise that this a version of a Robinson Crusoe figure—Defoe’s castaway, himself a former capitalist slave trader and coloniser, here bound by terra ferma rather than uncrossable oceans. This island is encased within another, with only interior pockets of water in which Crusoe can be cut adrift once more. The isolated lake becomes our Robinson’s inland ocean, one in which it is possible for him to transport himself, without leaving, without recourse, away from the relative safety of his island.

§ The lake’s appearance suggests innumerable questions: what is the colour of this water? How deep is it at the centre or at the edge? When does it freeze? Does any sunlight reach the bottom? What life hides beneath the surface? Is it fed by a stream? Is it thick with weed or barren like a crater sealed with rain?

§ In terms of composition the shot is as simple as it could be. The camera is static. A wide angle takes in the body of water only to a limited extent, its full dimensions not given to view. It may be anticipated where the raft will drift, once it has been manoeuvred out into the middle, such that its motions are kept in view at all times. The embarkation is watched coolly, without adjustment. Amidst the stillness, all disturbances in the water seem to be excessive, even if the figure’s movements are calm and methodical. Still they are not what might be called expert. The figure is not silent. He is not a natural predator. There is a sense that he is determinedly stepping into a medium that is not his own. Clearly this is an excursion into unusual territory; it is an extraterritorial gesture. The scene is photographed laterally, as it were, emphasising movement from side to side, in fact from left to right, as if encoded according to a Westerly drift. The flat silver basin is punctured as the raft proceeds toward the centre, achieving a certain degree of independence from the shore before the figure gently changes position, bringing his legs out from under him and leaning his upper body forward slightly. His final position is that of a man who has just sat up in bed, fresh from a dream.

§ You note that there would be a notable difference between the upright rafter, standing balanced with his stack of provisions, using a long oar to punt his way down the delta to the open sea, and one in a more lateral orientation—the figure lying prone—as if this position held some other significance. You have seen it elsewhere in the film too: our hero hermit clearing the clutter from a caravan bed in order to sleep in the middle of the day, photographed through dirtied glass as if to meld his features with the surrounding trees. Another scene sees his remote walk interrupted by another nap, the bearded figure suddenly lying supine in the heather. Is this the intermittent assumption of passivity? A purely practical necessity? And when later, on the makeshift raft, the figure is bent at the waist, perhaps this suggests that his passivity is now poised, as if his waiting is not that of the resting traveller or the man of leisure but the stance of one who tries to occupy territory between sleep and wakefulness. Adrift on the lake, the figure is awake and restful in the same moment. These are instances of taking pause, it seems, a process of positioning oneself outside the reach of one’s surroundings. Switched off, stepped out. A desert father cutting ties as he disappears into the shadowy sands.

§ The act of fishing seems incidental here, the line trailed into the water on one side of the craft more like a token anchor than a device for hunting. This slightest of filaments keeps this satellite from careening fully out of orbit, as its pilot risks being abandoned completely to the cycles of gravity that cushion the earth. This may be, in some way, what the film is about: orbiting states of proximity and the distances between one set of values and another.

§ Our near mute protagonist is Jake Williams, the isolated location Aberdeenshire in north east Scotland. It is filmed by Ben Rivers in 16mm, on five separate trips accompanied only by sound recordist Chew-Li Shewring. Each visit lasts between one and three weeks. The film rotates through the seasons, the production schedule adapting to changing conditions. Although there is no script, there is a list of possible actions and agreed-upon activities. This is Rivers’ first feature-length production. It returns to a subject he has filmed once before, in 2006, for the 14-minute film, This is My Land, in which Jake is seen in a similar scenario. The older film also has a title with a possessive emphasis, indicating perhaps that territorial boundaries and private ownership are the precursors for any consolidated individualism or alternative way of living. Whereas the tone was lighter in the previous film, with sequences more fragmented and speaking voices heard, now Jake is reticent and the shots are slow moving. Time is approached very differently. Any obvious anachronism in the “mythic time” being conveyed is effectively flattened and homogenised by the monochrome aesthetic.2 Rivers himself strives for settings that are, in his words, “undefinable in time”, and the use of black and white stock edges it further away from documentary, perhaps nearer to an avant-garde heritage.3 This is not ethnographic film-making, observing and recording a human subject; nor is this reportage. Our actor is not following direction. Yet his behaviour is clearly not unaltered. Scenes are the product of a collaboration that is not given, a mixture of genuine habit, plausible fantasy and a banal yet cinematic surrealism. There are levels of construction here that allow aspects of fiction to bleed into any seemingly standardised document of portraiture.

§ Much of Jake’s represented world is analogue, filled with an accumulated clutter of old cassette and record players, pen and paper. The presence of the hand is evident throughout. The filmstock is processed by hand too; inconsistent waves and blushes flare on screen, as if chemical signatures wafted across the images from time to time. We are connected here to the moisture of the eye, reminded of the transience of celluloid. As well as implanting texture to the images, there is an added emphasis on the physicality of the life we are watching: tasks that are common yet here seem to be elemental, hard fought. This is film-making that is hands-on yet intuitive, building up a composition of images and sounds as if physically constructing an object. From the build up of interconnected layers and represented depths, a cumulative language of “gestures and movements” seeks to occupy space in different ways.4

§ You then ask yourself, associations with Robinson Crusoe aside, what kind of solitude is being presented here? Certainly there is an emphasis on living with different forces—natural rhythms, weather conditions, fluctuating resources and so on—and this forms a kind of game of resistance and complicity that requires improvisation and adaptation, “intelligence, self-interest, prudence [and] foresight”.5 Yet rather than solitude it seems more like what Roland Barthes calls, in his 1977 lecture series on ‘How to Live Together’, a form of anachoresis, a ‘retreat’ that he describes as an “act or state, or concept [...] of separation from the world that’s effected by going back up to some isolated, private, secret, distant place.”6 Given that evidence of some low-level engagement with a wider community, no matter far off-grid he might be, we might say that this is what is being enacted in the walk to the fishing lake: an enfolded quality of separateness that exists within an already withdrawn mode of living. It is the image of an inner retreat within an outer one.

§ Barthes clarifies that anachoresis is “not a matter of absolute solitude, but rather of this: a way of reducing one’s contact with the world + individualism (individualistic asceticism)”.7 The latter is symbolised throughout the film in countless ways: evidence of character not only in physical appearance and the movements of Jake when on screen, but also the world of objects and spaces that he has surrounded himself with, and which we (as the watching camera) become part of. This kind of individualism is evidenced in a prosaic inventiveness, a personalised adjustment of the smallest details of existence such that they can then take on the unique colour of an independent life. If a retreat is sought when fleeing the state, the taxman or the army, whether or not it has to be earned by two years spent at sea, what the film shows is a phase of manual labour that comes after, one that might be closer in form and function to prayer, or even subjective activism. As Barthes suggests, this kind of retreat often constitutes an “individual’s solution to the crisis of power”, formulated as the precisely rendered objection or rejection to such power.8

§ You start to ask questions concerning the film’s relationship with sound or with field recording. You see that Chu-Li Shewring, the film’s sound recordist, is herself an artist and film director, often working in collaboration with Adam Gatch, Jeremy Deller and Patrick Keiller (a filmmaker with his own Robinson complex). Much of her other work evidences a similar tactic of forcing alignments and disjunctions between image and sound, often undermining and emphasising visual gestures with an auditory slapstick.9 As with various examples of this effect in other films, the composite sound design in Two Years at Sea is for the most part dominated by non-diegetic sound, where the source is not visible on screen and often not even implied by the action. Whilst the most common instance of this method—i.e. the voiceover—is something that Rivers uses often, this is here entirely absent. No accompanying testimony explains the imagery or links up the edit. Yet the definition of this type of non-diegetic sound is not quite straightforward. The film accumulates a presence of sound that can certainly be indirectly associated with the images that are seen on screen, even the world that is being represented. Yet the emphasis of these sounds is often slightly shifted; for example, postponed until a previously separated sound / image coupling are reunited, or where certain sounds are recorded from close proximity, therefore transformed from what might be considered more naturalistic forms of recording. The isolation of the sounds—say from a crackling fire, or snowfall in a forest—forces them to be more prominent that they might otherwise be. The concentration of the sound world we are presented with is inconsistent—it may seem naturalistic, as if we ourselves are there, listening in, yet the central point of this audibility shifts around the imagery as much as the edit chops and changes. Our attention, or our attentive listening is moved around the ‘space’ of the film like a piece on a game-board. Just how the coherent sound-world of the final mix is alien to the world we enter visually, may depend on our understanding of listening. What is it that could come from outside the ‘space’ of such a given environment, as we watch one image fold into another, two sounds overlaid, then a sequence where nothing seems to move or resound, and it is seems as though we are simply looking through a window?

§ If there is a tendency toward transparency in field recording, where sound might be let through without additional interference, then what would a technique of transposition—wherein ‘naturalistic’ recordings are played back separate from the images they link with, or where they precede or retrieve their visual counterparts—do to the transparency of the scenario being depicted? Of course, it is worth pointing out in relation to the technical methods being used, that more often than not audio is not being captured on the film camera. A 16mm Bolex camera does not bind image and sound together within the material apparatus of the device. The two need to be synced together subsequently (i.e. in the edit) for the ‘normal’ construct of sound and image to subsist. It is strange to think of this conjoined structure in terms of transparency—if we transpose the term from our comment on field recording—yet it may be helpful in allowing us to see how a certain sequence within a film, i.e. one where there is seemingly no interference with the image/sound coupling, may come across with more clarity or take on another significance.

§ In his Notes on Cinematography, Robert Bresson suggests that “one can not be at the same time all eye and all ear”, stressing that sound and image in cinema have the capacity to cancel each other out, when they should be put to work in a “sort of relay”.10 Bresson pitches eye and ear together as the malleable components to be used in different compositional structures in film. Where he claims that the “eye solicited alone makes the ear impatient, the ear solicited alone, makes the eye impatient”, Bresson urges the filmmaker to “use these impatiences.”11 But it is a process of “governable” modulation for the viewer too, and one that might be thought in terms of a kind of ‘floatation’ over and above shifting binary oppositions. All of this seems directly appropriate to the lake scene in Two Years at Sea.

[...] [silence, not silent, quiet elongated, un-cut]

Bresson gives a maxim: “Against the tactics of speed, of noise, set tactics of slowness, of silence.”12 It is perhaps these contingencies, imbalances between what is slow and what is fast, what is full of noise and what silent, that takes on added import for the castaway. Defoe himself asks, in a footnote ruminating on the speed of sound, in relation to Crusoe hearing cannon shot from a far off ship, “[d]oes sound move in a right line the nearest way, or does it sweep along the earth’s surface?” before himself giving an answer, saying that it “moves in the nearest way; and the velocity appears to be the same in the acclivities as in declivities.”13 Yet this assurance of clarity in the transport of sound does not seem to reassure us totally. Back at the lake, as we watch the raft occupy the disc of water like a floating fort on a sliver of mercury, we are left with time to speculate on the angle of the mic boom, the distance of the recording device from the shore, the thickness of a blimp against the wind, the polarities of the microphones. In the limpid transparency of the image, with its indexical traceable sound world, its meditative POV, we begin to ask to what degree such contingencies locate and emphasise certain details above others, the orders of dependency between image and sound, between one sound and another, let alone how such recordings might be combined in the image/sound mix.

§ The vulnerability of the makeshift raft, even on this mirror-like water, cannot help but make you think of the Dutch-American artist Bas Jan Ader, setting off across the Atlantic in his tiny one-man boat. There is no sense of crossing here, no traversal that need be accomplished, or valorised as the attainment of the ‘miraculous’.14 If the act of fishing has become incidental, there is a sense that the detachment from the land is something more akin to a ‘circling’, something more to do with magnetic fields, a combination of resistance and attraction, the raft floating close to a central point only briefly, before drifting inevitably to the edge. It may be blown by winds but may also follow a radiating energy that is distributed between the mass of water and the land it covers. Witnesses to this slow moving centrifugal force, we watch the needle move outward, a long player revolving with the planet, as the free floating space capsule moves toward the bank. There is in this scene a sense of resumption—of there being a plane upon which the gravitational slump would come to rest. But actually it is this assumption that is undermined, as the sought after balance point is itself subject to axial forces, sliding the craft away from equilibrium.

§ You wonder what could be made of similarities between the way the lake scene is composed—specifically in relation to an earlier shot taken from the window of Jake’s cabin, with staggered tree-lines in the distance, looped by low cloud—where the landscape takes on something of the anthropomorphic imagery of Man Ray’s surrealism. You think particularly of his 1934 painting entitled Observatory Time (The Lovers), a tribute to his former lover Lee Miller. The elongated lips of Miller’s mouth, pursed together, float above the tilted landscape, the bundled domes of an observatory building at the lower left of the canvas, echoing Jakes belongings piled at the side of the water. But there are other references to painting too. In the montage documenting Jake’s approach to the lake, there are repeated shots of him carrying his equipment, with floatation devices slung around his waist and the wooden frame balanced on his head. Not only is this reminiscent of the dexterous efficiency displayed by people travelling long distances to find water, there is something anachronistic about his gait and appearance, particularly the close-fitting hood. He becomes something of a figure from the middle ages, or the early Renaissance, to be found in Breughel’s winter landscapes or a wayfarer imagined by Bosch. Worldly attachments are strapped to his body, reduced by experience and utility. The determined pedlar becomes the itinerant wanderer of Romantic legend. Yet there is also something routine about his procession, as if this were a regular journey that took in certain territories according to a specific schedule. The task may be nothing out of the ordinary. The way the journey is compiled, with multiple shots of the lone figure traversing the landscape from one edge of frame to the other, ties in with Rivers’ stated admiration for Bruce Baillie’s Mr Hayashi (1961), a three-minute portrait of an individual punctuated by rhythmic traversals of the framed landscape.15 In both films, as well as shots of a walking figure being followed (or ‘pulled’ toward the camera) at close quarters, the edit is often dictated by the time it takes the subject to walk from one side of the image to the other. This gives such a predictable structure to each sequence that the viewer becomes overly sensitive to any deviation from such manifest timings—an example being when Rivers does not cut when Jake’s raft touches the side of the lake but waits until he pushes off once again, back out into the wilderness.

§ Origin of the Species from 2008 is again shot through the seasons, this time in the “garden of S., who lives in the wilderness and builds contraptions”; the ingenuity and work ethic that occupies the centre of Philip Trevelyan’s The Moon and the Sledgehammer (1970). Improvised camera angles, using tractors as cranes, using only natural light; where the camera became part of the furniture (yet at the same time the filming became the main event in that closed community). Exploration into the nature of the world; the enthused and awed thoughts about Darwin and evolution providing an odd counterpoint to the creationist thoughts gently expressed by one of the sons in The Moon... The comparisons with that film are subtle but consistent, not only with the general air of work, idiosyncratic labour directed at odd inventions, large-scale contraptions and potentially aimless constructions—a metal boat in one, a Heath Robinson pulley system in the other—but also the elaborate use of a circular saw, power units somehow rigged up in clearings, interiors being swamped by no other concern than for the ongoing (and endlessly deferred) practical task. Against the morphogenesis, the impossibility of nothingness becoming the world, there is stacked the solution of time. Voiceover that occur over the telephone, then in clearer audio. Taking in references to Darwin and quantum physics, these are still gestures of survival.

§ As well as a hopeful pessimism about the present and a taste for visionary post-apocalyptic wreckage, a key theme in Rivers’ film work is the importance of written (and spoken) text and the cinematic presence of the book. Almost all take a text as their starting point. Two Years at Sea is partly based on a reading of Knut Hamsun’s Pan, a symbolic novel that begins with an individual living alone in a forest hut, leading to Rivers’ short-lived desire to locate and film a hermit in Norway. More general influences might come from the writings of J. G. Ballard or even Russell Hoban, and combine with utopian/dystopian fiction, building up into the necessary features of individual films. The 2015 work, There is a Happy Land Far Awaay, takes as its foundational text a prose poem by Henri Michaux: ‘Je vous ecris d’un pays lointain’ [‘I am writing to you from a distant country’]. Rivers’ film is constructed from footage of the remote sub-tropical island of Vanuatu in the South Pacific, subsequently devastated by Cyclone Pam in March 2015. Michaux’s poem is an epistolary account of a strange otherworldly place, detailed a surreal description of somewhere absolutely other but which could also be a familiar world made strange. The text—one of what Paul Auster calls Michaux’s “imaginary anthropologies”—contains a plaintive emphasis on sound.16 In one section, the female narrator relates that: “At night the cattle make a great bellowing, long and flutelike at the end. We feel compassionate, but what can we do?”17 This uncertainty is embraced in Rivers’ film, the voiceover repeatedly rehearsed by an awkward female voice, the final recording including hesitations, repetitions, bursts of laughter and interjections from the director. The additions bring another layer of complexity to an account of already irretrievable distance. It suggests that the voyage to this distant land continues, even when images of the fabled destination are before us. We are presented with a composite impression of the island, with stretches of jungle and active volcanoes—their deafening eruptions often making the voiceover inaudible. There are landscapes of ash, submerged wartime vehicles, half-wild piglets feeding in the mud. The result is somehow apocalyptic and idyllic. We watch a small group of children stroll across the shallows of a river delta, which widens out behind them until it meets the sea in the distance. The viewer might be convinced that these youngsters are crossing near the very edge of the (flat) earth, warily at ease with the end of the world just over their shoulders. As well as the opening sequences of Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998) in which American soldiers wander in philosophical unease amongst island tribes before battle, there are echoes here of Werner Herzog’s La Soufrière—Warten auf eine unausweichliche Katastrophe [‘La Soufrière—Waiting for an Inevitable Disaster’] (1977), based on the impending volcanic eruption on the island of Guadeloupe. The three outliers that Herzog encounters, each with their own reasons for not evacuating the island, seem like similarly incongruous yet powerfully symbolic inhabitants of a place very much out of kilter with regular expectations of space and time.

§ In Rivers’ 2008 film, Ah Liberty!, the soundtrack is again, for John Hutchinson, “illogical [...] combining unsynchronised voiceover with unexpected moments of silence, hints of equipment noise, and oddly inappropriate fragments of music borrowed from old movies.”18 It may be that the film’s title is a quotation from Robert Pinget’s 1958 novel, Baga, a satirical story about a laughably disengaged King drifting through his duties, doing little but eating, sleeping and watering his plant, propped up and misdirected by his Prime Minister, Baga. After sleepwalking into war, the King retreats into solitude and senility in the woods before eventually returning to the throne as if nothing had happened. Early on the King exclaims: “Ah, Liberty! Liberty is the absence of ideas. That’s what I like best.”19 Again it may be that the appeal to an ‘unthinking’ mode of existence—which is to say a somehow innocent, quiet, non-destructive or conniving life—is what Rivers has recognised. The King elaborates further on his liberty: “I have fallen back on the things I used to like, which are not ideas. And I cultivate them. They are feelings. Or rather, impressions. The impression of well-being. The impression of understanding. That’s the real life.”20 It may also be that this corresponds with Rivers’ own method, particularly when generating combinations of sound and image. In an interview with Frances Morgan, Rivers suggests that, for him, sound “comes together after a process of playing with the material, often trying sounds which may be in disjunction with an image, following uncertain feelings which can be tried out quickly with Final Cut Pro.”21 This seems pleasingly similar to the quiet (yet mad!) King’s liberty, away from the role for which he is irretrievably ill-suited—an appeal to ‘uncertain feelings’ as a form of understanding, however fleeting it may be.

§ Ah, Liberty!, Rivers’ own document of this kind of understanding sees a group of masked children playing with abandon in an undesignated time and location, perhaps in the edgelands of an undisclosed civilisation. Again we could be watching ancient hinterland dwellers or the survivors of an apocalypse. Yet theirs is an isolation without loneliness. A small community exists (arguably closer to Barthes’ vision of a small, idiorhythmic group), living close to animals— lizards, dogs and horses—and half-forgotten machinery piled up in technology graveyards. This is an existence that has reset, finding its own way forward with available resources, without reference to broader social or political conventions. It is shot in myth-making sepia, the imagery and sound tending towards the primal and the primeval as well as the romantically idyllic. Bordering landscapes are shown to be large-scale, near sublime, defining the limits of this self-contained world, hemming it in with stretches of water and forest. The masked imps may well be to nature but their world is also cartoon-like and potentially savage. The film echoes Two Years at Sea at various points, with some shots appearing as if exactly replicated. Again the seasons are accounted for. Sloping rain falls against banded landscapes, watery expanses clipped by forest verticals. There is a hint of pareidolia, seeing faces in passing clouds; the image of fire becomes emblematic, as does its magnified audio. There are shots of a baby lying prone in amongst stones, another passive assumption of liberty.

§ There are associated similarities between Two Years at Sea and Lisandro Alonso’s La Libertad (2001), another film said to be an influence on Rivers’ work. Alonso’s film shares the same affectionate focus on the passage of time, particularly spent at work, with daylight hours filled with tasks, a sense of forward motion, of need and necessity. Much like Two Years at Sea, the final scene sees the silent protagonist—a woodcutter whom we have followed stoically through his daily routine—sits by the fireside, an electrical storm gathering in the background. Instead of a drawn out fade to blackness and silence as Jake’s fire turns to embers, here a thunderclap and the first fizz of rain accompanies an instant cut, followed by the film’s title emblazoned like a descriptor of the day-in-the-life that has just been witnessed. These final sequences both use the cliché of recorded fire, with its recognisable close-mic-ed intricacies. Yet the insistence of both film-makers seems to rescue it from being clumsy. The wordless face of Jake passes through a complex range of expressions, from introspection, maudlin recognition of the camera, calm contentment, distracted reveries, and so on. The sound of the fire seeps like an inconsistent rhythm underneath, for you reminiscent of the sound of a group of turnstones feeding on a shingle beach, their adept rotating of pebbles forming a delicate fizz that can be heard clearly over the rotary waves behind. The slow fade of this last scene in Two Years at Sea stands in contrast to the scene at the lake. The finale is darkly enclosed and intimate, whereas the lake is brightly exposed and open. You think of another line from Pinget’s novel, where the semi-reclusive King is contemplating music that is being played in the forest: “The forest should amplify the sound, but in fact it muffles it. At first one finds this music sad. But not afterwards. It no longer expresses anything. It’s like the sound of a faint wind, its lamentation forgotten, or stones in the mountain.”22

§ Slow Action (2011), the film Rivers completed just prior to Two Years at Sea, departed from his habit of using location sound that has been specifically recorded. Instead he used sonic reference points from existing cinema, all music being lifted from existing films, mostly science fiction movies from the 1970s. The film consists of four fictionalised accounts of islands, bringing together footage from real locations with voiceover composed by science-fiction writer Mark von Schlegell. The text details the nature of these symbolic islands, curating them as entries in what von Schlegell calls The New Earth Encyclopaedia of Preserved Utopias, making reference to all manner of literary antecedents from Herman Melville, Jonathan Swift, Jules Verne and Samuel Butler.23 Again there is a deliberate and carefully modulated disjunction between what is seen and what is heard: combinations of voice, sound, image and movement that have no doubt emerged in the editing suite, rather than being defined in advance. The consistent appeal to founding texts is satirised in the final section, which details the civilization of ‘Somerset’, an island that Rivers invented and conveyed through footage constructed in his home county of the same name. The voiceover claims that certain sects in ‘Somerset’ were founded from four seminal publications—Leon Trotsky’s The Permanent Revolution (1931), Jean- Jacques Rousseau’s Confessions (1782), Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) and Zitsko’s No Frontier—with each book washed up on the shore, found inside a trunk with a newborn baby. Of course the latter is an invention, von Schlegell describing it as being “now lost to Somerset”, as if emphasising that even fictional foundations are subject to entropy and loss.24

The image and act of reading has significance in many of Rivers’ films, as well as being prominent in the work of his influences. Jake is seen poring over books inside his home or reading in the sun-filled yard. The painter Rose Wylie reads aloud n Rivers’ most recent filmic portrait, What Means Something (2015), included in ‘Earth Needs More Magicians’, an exhibition at Camden Arts Centre. It is possible to link this with image from Margaret Tait’s 1952 Portrait of Ga, a four-minute account of her elderly mother living alone in the Shetland Islands. Again the protagonist is shown reading from a book, held open on the lap, its pages edged in red, with the words just visible on the screen:

Chapter 1

A Theory

Once more this suggests something powerful in relation to what Rivers’ seeks to extract from literary texts in his film works: an appeal to theoretical material (the ideas rejected by Baga’s King) through the gritty, lived-in, labour in the practice of everyday life. This is the impact of literary culture, how it may provide the preliminary labour (‘at sea’!) of instructions as to how to live, how to survive, in the face of increasing pressure from civilisation at large.

§ As a final thought, you go back to Baga, recalling that the King, toward the end of the novel, had started to build a raft, hoping to escape his office. He is forever finding fault with it, developing a paranoid mistrust of his materials, before the impulse to escape is forgotten and the raft never mentioned again. You also think once more about the raft seen on the lake, trying to imagine it as a sonic phenomenon of some kind: the concavity of the land pointing skyward, Jake skating on top of a speaker cone. You see his faint fishing line as just another part of his function as a stethoscope on the live surface of the water. Rivers describes his films as propositions, yet you find it difficult to proposing any concrete commentary on the sound of this scene in isolation from all tht surrounds it or how it relates to the entirety of the film. You quote the King once more, as you speculate as to the specific qualities of his speaking voice, even as you ‘hear’ it inside your head as you read: “But it’s difficult to talk about sounds.”25

Notes

1 Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, Edgelands, 2011, London: Jonathan Cape, 72.

2 Andréa Picard, ‘A Man Apart’, Sight and Sound, May 2012, 24.

3 Frances Morgan, ‘Sound on Film: Listening to Ben Rivers’ Slow Action’, np. <http://www.soundandmusic.org/features/sound-film/listening-ben-rivers-slow-action>

4 Picard 2012, 24.

5 Roland Barthes, How To Live Together, Session of January 19th 1977, 14-15.

6 Ibid. [Barthes, Session of January 26th 1977, 24]

7 Ibid. [Barthes 25]

8 Ibid. [Barthes 24]

9 Cf. Mantis Tales.

10 Robert Bresson, Notes on Cinematography, trans. Jonathan Griffin, New York: Urizen Books, 1977, 62.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., 63.

13 Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe: The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner who Lived Eight-and-twenty Years All-alone in an Uninhabited Island on the Coast of America. J. Gold & J. Mawman, 1815, 160.

14 Something about Bas Jan Ader and the surrealist ‘marvellous’...

15 Baillie [http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xqltf_mr-hayashi_creation]

16 Paul Auster and J. M. Coetzee, Here and Now, 2015, London: Vintage, 215.

17 Henri Michaux, ‘I am Writing to you from a Distant Country’ in The Swanee Review, Vol. 57, No. 4 (Autumn 1949), Johns Hopkins Press, pp660-664.

18 John Hutchinson (2013) Ah, Liberty! Dublin: Douglas Hyde Gallery, np.

19 Robert Pinget, Baga, 1967, London: Calder & Boyars, 6.

20 Ibid.

21 Morgan, np. [My emphasis]

22 Pinget, 63.

23 Frieze, Issue 141, September 2011, 140-145. The three islands upon which much of the film is based are Lanzarote, Gunkanjima and Tuvalu.

24 Ibid.

25 Pinget, 63.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YHNfaMxTSg]

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwGNAIbe-xQ]

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6-8Qn8YQN8]

The Hyrcynium Wood (2005) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Gs5M92-rts

House (2006) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkQjOhzDSRY

Ah Liberty! (anamorphic 16mm film with sound, 19 mins)

There is a Happy Land Far Awaay (digitised 16mm film with sound, 20 mins)

Origin of the Species (16mm, 16min, colour, 2008)

Written for the 'Sound I’m Particular' lecture series, curated by Patrick Farmer, Oxford, 2016.