37.5 Fragments Toward an Occupation of Time

(01’00”)

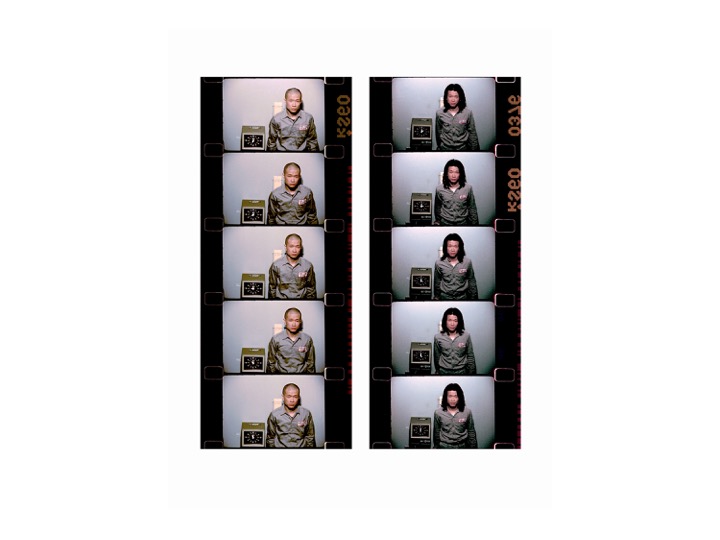

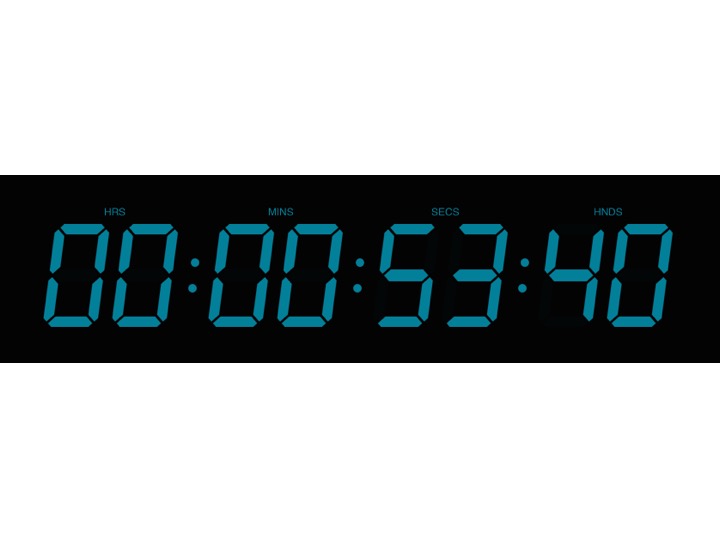

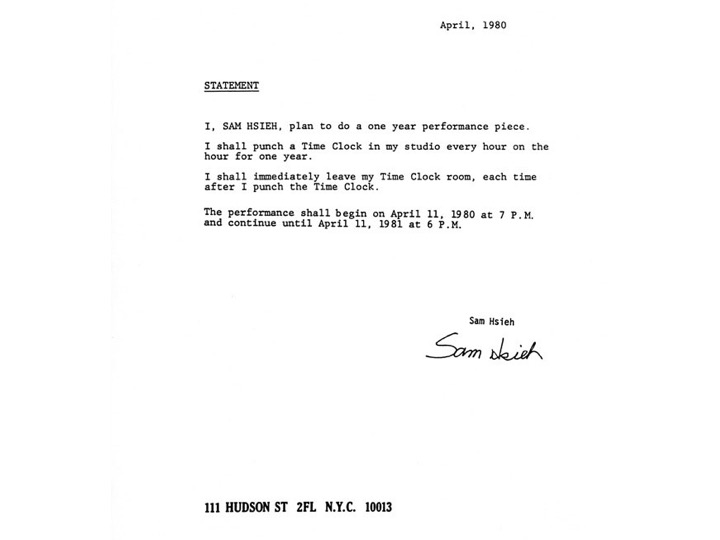

Taiwanese-American artist Tehching Hsieh entered the United States illegally. His precarious status informed his series of year-long performances, staged between 1978 and 1986, concerned with ideas of marginalisation and immigration, confinement and labour, employed time and free time, and so on. This series of so-called ‘lifeworks’ involved unprecedented physical difficulty: one year of solitary confinement; one year living outside with no shelter; one year tied to fellow artist, Linda Montano, without ever touching. Yet his One Year Performance 1980-1981 seems important to highlight: for a year the artist was obliged to punch a time clock, every hour on the hour. The work tied him to a physical location (his studio), to a rigid temporal regime and a written contract of self-employment.

(00’22”)

A question is asked: If time is considered as a material, does that then make it possible to alternate, interrupt, rebuild or occupy it?

A further question is appended: If time is occupied, is it being claimed as property or would it be relinquished once an implied protest has been acknowledged?

(00’45”)

During a conversation with an artist (who works part-time in a bank) it was suggested that the conventions of paid employment might be used as a series of productive constraints, markers against which it might be possible to define one’s creative activity. She suggested that the facilities of a workplace could be subverted, either openly or by subterfuge, such that, rather than a practice being shaped by the free time that regular employment provides, the everyday mechanisms of a paid position could be absorbed into the nature of that practice. After she declared this, the artist took a drink from the Coke she was holding, spilling some onto her business suit.

During a conversation with an artist (who works part-time in a bank) it was suggested that the conventions of paid employment might be used as a series of productive constraints, markers against which it might be possible to define one’s creative activity. She suggested that the facilities of a workplace could be subverted, either openly or by subterfuge, such that, rather than a practice being shaped by the free time that regular employment provides, the everyday mechanisms of a paid position could be absorbed into the nature of that practice. After she declared this, the artist took a drink from the Coke she was holding, spilling some onto her business suit.

(00’25”)

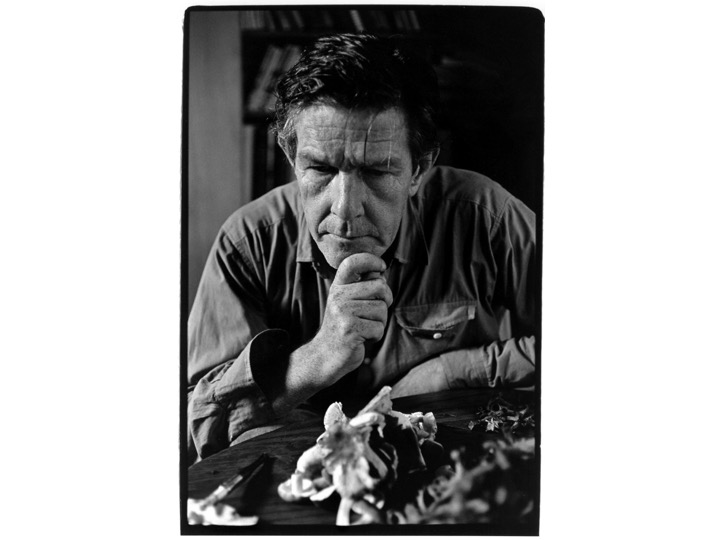

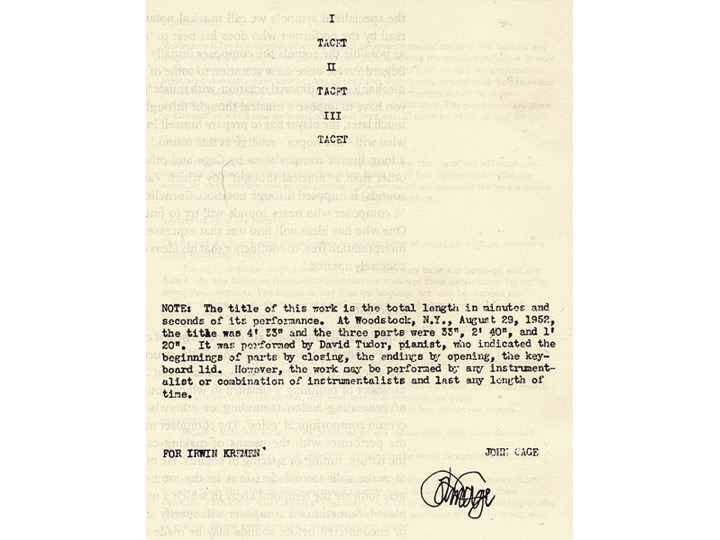

The composer John Cage, an enormously influential but still controversial figure, began in the 1940s to organise his music according to lengths of time in various proportions. He justified this with a polemic against Beethoven made in a lecture at Black Mountain College in 1948, in which he asserted that "[w]ith Beethoven the parts of a composition were defined by means of harmony. With Satie and Webern they are defined by means of time lengths. The question of structure is so basic, and it is so important to be in agreement about it, that one must now ask: Was Beethoven right or are Webern and Satie right? I answer immediately and unequivocally, Beethoven was in error, and his influence, which has been as extensive as it is lamentable, has been deadening to the art of music."

(01’05”)

In a Note accompanying his score for 4’33”, John Cage writes that the performer, David Tudor, “indicated the beginnings of parts by closing, the endings by opening (...)” the keyboard lid. There is something compelling about the availability of the keyboard indicated here; as described, the piano becomes an object that is passive in its ostensibly active parts (as in not immediately present for the conventional sound-making procedure of depressed keys: i.e. it is closed-off). It follows that the piano is conversely a potentially active agent in the sections between parts, where the keys are open to the air or to accidental touch―i.e. not in storage mode. The piano is taken out of commission in various stages of the score but is re-designated as active not only outside the piece (i.e. when the duration ends and the instrument is reset for other pieces), but also within its peripheral and interstitial moments. This seems to suggest some kind of proposition in terms of whether the piano is being rendered ‘available’ for work or not.

(01’06”)

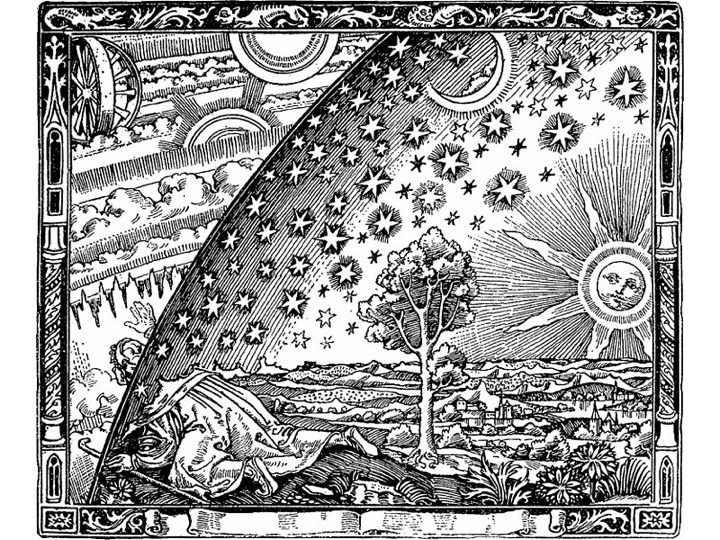

It emerges that one of the artists’ concerns is that the allocation of productive and unproductive time doesn't follow the paradigm of conventional work. This model, she argues, is based on a clear distinction between work and leisure, yet she finds herself working on the border between the two. She then makes a connection to Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things. The six books that comprise this epic poem are paired, with odd-numbered books presenting basic doctrines and even-numbered books presenting deductions made from those doctrines. Books 1 & 2 deal with Matter and Void; Books 3 & 4, Mind and Spirit; 5 & 6 with the Terrestrial and the Celestial. This structure also echoes the poem's content. The artist suggests that Lucretius’ use of conjunction does not indicate dichotomy but rather combination, and that he uses it to demonstrate the complementary aspects of a single reality: that void cannot exist without matter, that matter cannot exist without void. She concludes by saying “it’s the same with work.”

(01’11)

In ‘The Architecture of Silence’, a short text written in 1998, Swiss composer Jurg Frey writes of the “time-present” of a piece of music, wherein the “time-space of sound and the time-space of silence appear in their own particular realms”. Frey is a member of Wandelweiser, an international collective of composers founded in the 1990's, with a shared interest in the music of John Cage and its impact on contemporary composition. The significance of Cage’s 4’33”, first performed in 1952, lies in the removal of all non-essential characteristics of music. Having “left the musical rhetoric behind”, Frey observes, “there is instead a sensitivity for the presence of sound and for the physicality of silence”. He also notes that “there is no silence through production. Silence is just there, where no sound is.” This suggests that the production of one physicality is created by the negation of another―the negation of sound or of silence. Therefore, the “time-present” of the composition concerns the placement and displacement of material―that is, the placement and displacement of space, and of time.

Frey, J. (1998) (trans. Pisaro, M.) ‘The Architecture of Silence’. [http://www.wandelweiser.de/_juerg-frey/texts-e.html#THE] Accessed March 2014

Frey, J. (1998) (trans. Pisaro, M.) ‘The Architecture of Silence’. [http://www.wandelweiser.de/_juerg-frey/texts-e.html#THE] Accessed March 2014

(01’25”)

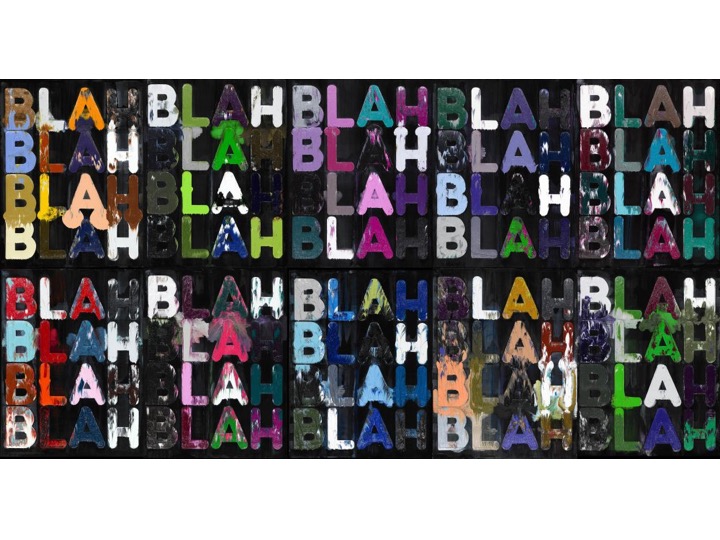

What is meant when art and life are spoken of as simultaneous? Is it the ambition to weave an aesthetic sensibility into all activity or rather the forging of a sense of self in the shadow of a cultural paradigm? The former is arguably implicit whereas with the latter comes a risk of forcing an uncomfortable imposition on everyday life. The so-called ‘total work of art’, where art and life become synonymous, has been claimed by commercial interests and appeals to lifestyle purchases… embroiled with contemporary consumerism to such an extent that the potential artist is already stripped of their alterity. The very idea of an artist-subject has been commodified...

In a time when the commercialisation of art practice is prevalent, and the art market dominant, the artwork-commodity is in danger of precluding work that doesn’t fit the system.

In a time when the commercialisation of art practice is prevalent, and the art market dominant, the artwork-commodity is in danger of precluding work that doesn’t fit the system.

(01’13”)

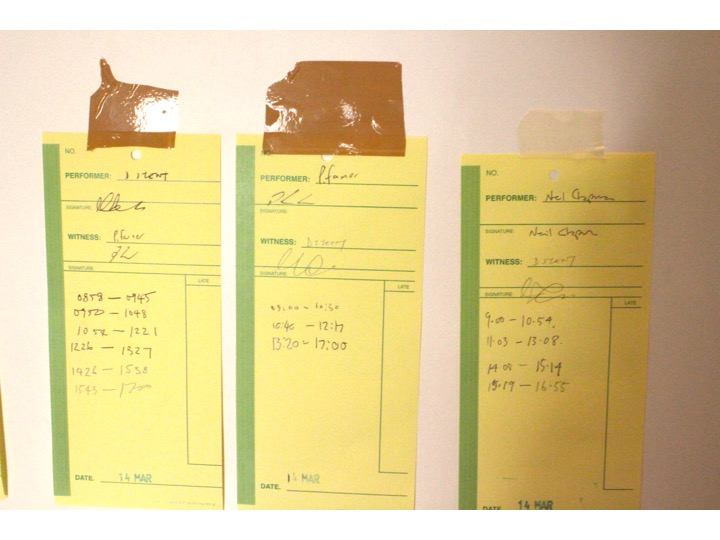

When thinking of the appropriation of workplace conventions in Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980-1981―time clock machines, punch cards, office uniforms, and security cameras―we might ask what he was doing in the intervals between these hourly gestures. Was his output, as it were, restricted to these acts or was he moonlighting on the side? The appropriation of only the formal structure of conventional employment―a temporal schema―provides the only ‘content’ in Hseih’s work. In this sense, time has indeed become the artists’ medium. Yet it was still necessary to appeal to third parties (if not direct employers) in order to keep track of his progress and ratify the authenticity of his work. All of the artist’s durational performances relied on the use of contracts; each of his punched cards were witnessed by signature. Even as his own employee, Hsieh’s works ironically implicate the ever-present bureaucracies of regular employment, emphasising the dominance of capital as well as the systematic procedures that bind the activities of the legal alien, registered citizen and surveilled subject alike.

(00’39”)

The title ‘Writing as Occupation’ is given to a series of collaborative residencies in which the activity of writing is posited as a means to explicitly occupy both time and space. The theme of occupation is a way of drawing attention to the time of writing, to focus on writing’s practice, yet the resonances with recent protest are also important, indicating an interest in exposing alternative forms of work, production and education. ‘Writing as Occupation’ invokes questions concerning the politics of experimental practice and the necessary labour of creative work.

(00’46”)

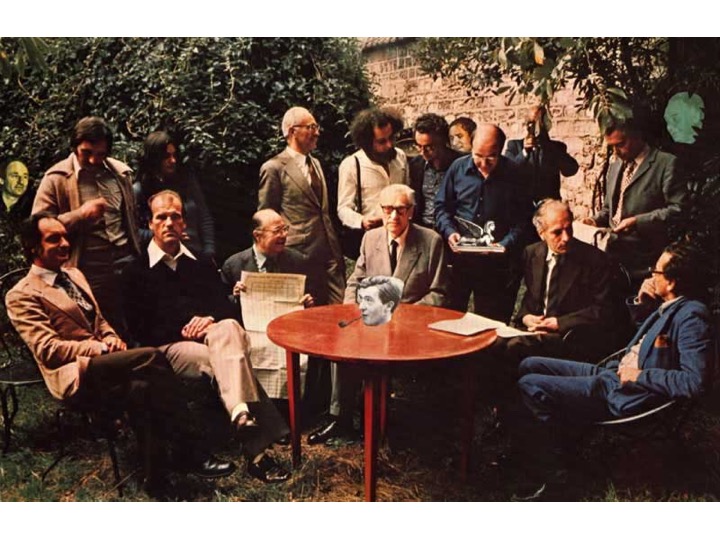

As the conversation progresses, the artist suggests that the use of conventional employment as a generative constraint might even be related to the literary work of the OuLiPo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle), which she quickly translates as the ‘Workshop of Potential Literature’. She immediately describes a project she is working on which involves making a model of what the OuLiPo ‘office’ might look like. Her work on the project is described as “exhausting”. Nonetheless, she is often heartened by the knowledge that Georges Perec, one of the most renowned members of OuLiPo (famous for writing a full-length novel without a single letter ‘E’), continued in his job in a University science library for some 17 years after his books were in print.

(01’17’)

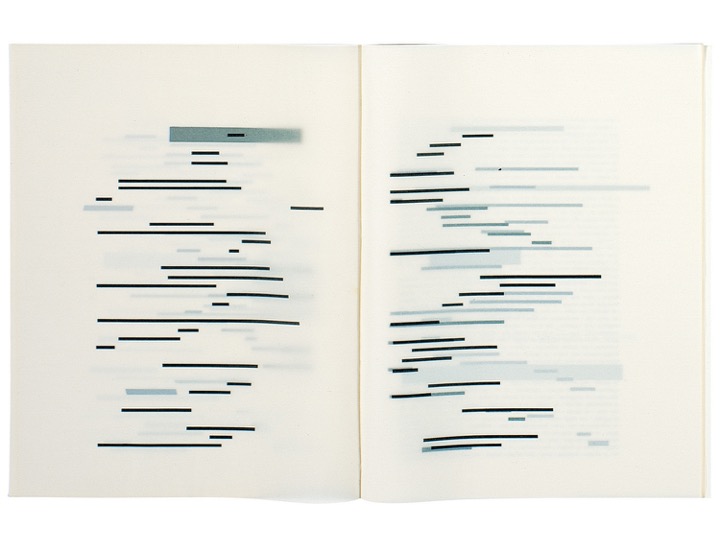

One strand of contemporary composition involves the use of scores that are mostly, or entirely, comprised of words. Such ‘text-scores’ can be poetic, intended to inspire instinctive or emotional responses in the musicians, or simply convey a series of instructions. Time and place can be indicated with a huge range of specificity―exact clock timings might be given, or reference to days of the week, or the seasons; time might be specified mostly in relation to other events (‘before’, ‘during’, ‘after’); the length of a piece might be determined by the time it takes to perform a certain action: ‘for as long as it takes’; a score might simply say 'for a long time'; or, like Stockhausen’s Verbindung, you might be required to ‘play a rhythm in the vibration of the universe’. Nam June Paik has even written a piece with durations measured in millions of years. Alternatively, time might not be mentioned at all, the length of a performance being left entirely to the performers, guided by what they feel the score implies or makes possible.

(00’51”)

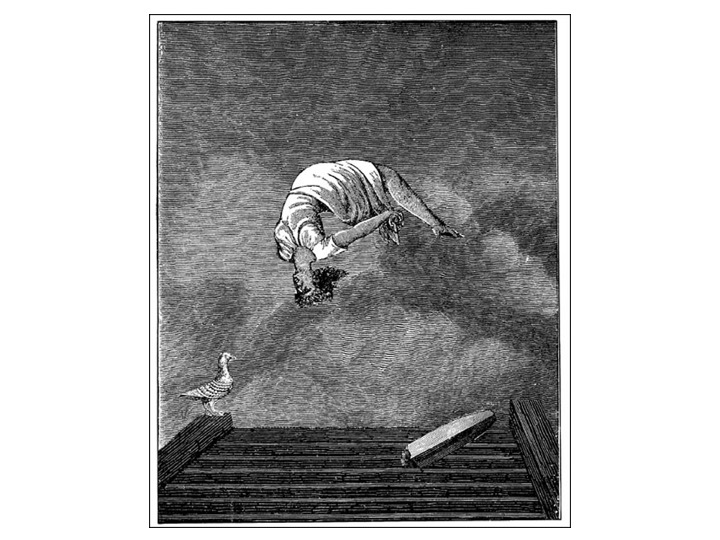

An image of precarity or ‘groundlessness’ accompanies many descriptions of artists who experience the familiar struggle of balancing ‘making a living’ and ‘making work’. There is a likelihood that such artists find themselves working without security, subject to zero hours contracts, low pay or exploitation. This is even before work has been under-sold, material and installation expenses recuperated, and studio rents paid. However, one must be clear that this is the precariousness of the artist (not the general worker) and, with that, recognise that there are two ways to experience freefall. One could be falling at great pace toward an uncertain ground or one might be suspended in an illusory sense of stability: the body that keeps falling, seemingly without end, soon stops screaming.

(00’59”)

German artist Hans Haacke’s early work, Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, exposed the dealings of the Shapolsky family, who owned a large number of slums in New York City from the 1950’s to the 1970’s. The work was due to be exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum but the exhibition was cancelled and the curator sacked. Officially this was due to the work’s ‘lack of neutrality’, but it was rumoured that the Guggenheim Trustees were somehow involved with the real estate group. In contrast, Haacke’s winning commission for the fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square will be exhibited throughout 2015. A bronze horse skeleton with a stock exchange ribbon tied to its leg is said to be a commentary on the relationships between art, finance and society. Boris Johnson, Mayor of London and commissioner of the fourth plinth, hailed Haacke’s work as “wryly enigmatic”.

Brown, M. ‘Trafalgar Square's fourth plinth to show giant thumbs up and horse skeleton’ in The Guardian, 7th February 2014 [www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/feb/07/riderless-horse-giant-thumb-fourth-plinth-trafalgar-square]

Brown, M. ‘Trafalgar Square's fourth plinth to show giant thumbs up and horse skeleton’ in The Guardian, 7th February 2014 [www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/feb/07/riderless-horse-giant-thumb-fourth-plinth-trafalgar-square]

(01’17”)

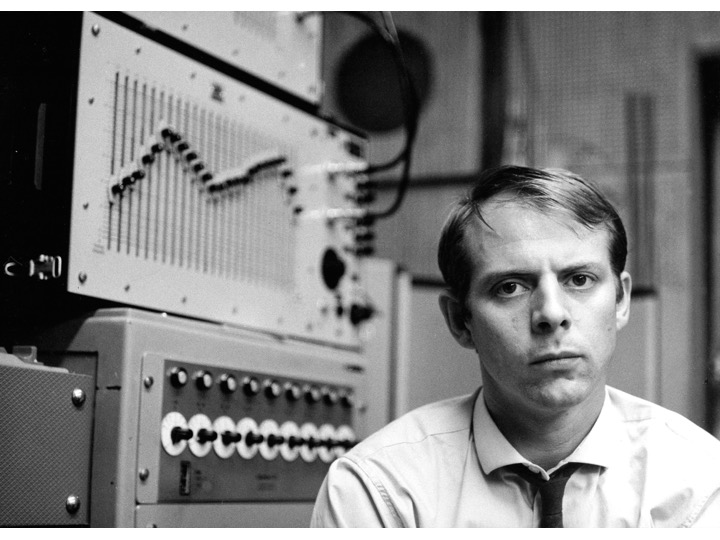

The stopwatch has long been a common accessory in certain kinds of experimental music. There is, however, a distinction to be made between scores which specify the use of timekeeping devices and those that employ specific timings but are open to―or specifically request―performance without use of a clock. Swiss composer Manfred Werder (a member of the Wandelweiser collective) now works mostly with text-scores consisting of found material, but for many years he wrote pieces divided into regular blocks of sound or silence. He prefers, however, performers not to use watches so that they listen closely to each other and explore their own sense of time, highlighting the distinction between the stark perfection implied by the score and the messiness of actual human performance.

(XX)

Set theory originated in Georg Cantor’s work on infinity in the late nineteenth century. If we consider groups of things that can be paired off one-to-one with each other to be, in some sense, of the ‘same size’ (even if the groups are infinite), then we can find examples of infinite sets which can be put into just such a relationship: for example, all the counting numbers 1, 2, 3, etc. and all the even numbers 2, 4, 6, etc. We can also find others which cannot. The set of all infinite decimal numbers (including pi, the square root of two, and so on) cannot be put into such a one-to-one relationship with the counting numbers, and so can be considered as a “larger” infinity. This led to the considering of all mathematical objects as various kinds of sets. These ideas are of importance to many of the composers associated with the Wandelweiser collective. This connection, plus the more prosaic fact that the group takes different forms for different performances, rather than having a fixed membership, suggested the name The Set Ensemble.

Set theory originated in Georg Cantor’s work on infinity in the late nineteenth century. If we consider groups of things that can be paired off one-to-one with each other to be, in some sense, of the ‘same size’ (even if the groups are infinite), then we can find examples of infinite sets which can be put into just such a relationship: for example, all the counting numbers 1, 2, 3, etc. and all the even numbers 2, 4, 6, etc. We can also find others which cannot. The set of all infinite decimal numbers (including pi, the square root of two, and so on) cannot be put into such a one-to-one relationship with the counting numbers, and so can be considered as a “larger” infinity. This led to the considering of all mathematical objects as various kinds of sets. These ideas are of importance to many of the composers associated with the Wandelweiser collective. This connection, plus the more prosaic fact that the group takes different forms for different performances, rather than having a fixed membership, suggested the name The Set Ensemble.

(01’10”)

A process of composition is involved in the specific placement of objects in a sculptural installation. Such a deliberate organisation of materials offers an explicit consideration of spatial distributions, yet its articulation in relation to time might be more difficult to recognise. One way to think about such compositions in terms of their arrangement of (or through) time could be to see them in terms of grammar. Whilst they might not be clear sentences with fixed rules about reading order or structural orientations that produce sense (or even non-sense), these installations might offer coordinates for another kind of abstracted ‘statement’. Although it may be ‘written’ across the space in some way, this statement cannot be read as anything other than a conveyor of an adjunctive process relating to the combination of space embedded in time, and vice versa.

A process of composition is involved in the specific placement of objects in a sculptural installation. Such a deliberate organisation of materials offers an explicit consideration of spatial distributions, yet its articulation in relation to time might be more difficult to recognise. One way to think about such compositions in terms of their arrangement of (or through) time could be to see them in terms of grammar. Whilst they might not be clear sentences with fixed rules about reading order or structural orientations that produce sense (or even non-sense), these installations might offer coordinates for another kind of abstracted ‘statement’. Although it may be ‘written’ across the space in some way, this statement cannot be read as anything other than a conveyor of an adjunctive process relating to the combination of space embedded in time, and vice versa.

(01’35”)

In December 2013, five members of the protest group ‘Future Interns’ dressed as Father Christmas and gathered at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Their protest concerned the advertisement for an internship requiring previous experience and some expertise in the area of contemporary art. It was felt that the recruitment of a volunteer to fulfil a role vital to the gallery was exploitative. The gallery subsequently released a statement offering their apologies and explaining that the advert was not in line with their current terms for volunteer placements. At the time this statement was made the Independent published an article revealing that the director of the Serpentine, Julia Peyton-Jones had received a 60% increase in pay since 2011, bringing her earnings, after a bonus and other benefits, to around £150,000 per year. The gallery itself receives an annual £1.2 million from Arts Council England as a regularly funded organisation. Questions may well be asked as to whether that money could be put to better use.

(00’52”)

During a conversation with the artist, the story of Emmalee Bauer is mentioned, an employee of the Sheraton Hotel in the city of Des Moines in the United States. Some years ago, Ms Bauer was fired from her position for using her employer’s computer to keep a journal that scrupulously recorded all of her efforts to avoid work. Bauer transcribed and annotated great chunks of time in this manner, eventually compiling a 300-page single-spaced document, extracts from which were read out during her judicial hearing: “This typing thing seems to be doing the trick,” she wrote, “it just looks like I am hard at work on something very important.” Arguably she was. Yet if her book-length work hits on the “separation of labour from desire”, it might also suggest something like a ‘lining’ to regular work that is there to be activated in any number of forms and gestures.

Wark, M. (2013) The Spectacle of Disintegration. London: Verso, 5.

Wark, M. (2013) The Spectacle of Disintegration. London: Verso, 5.

(00’50”)

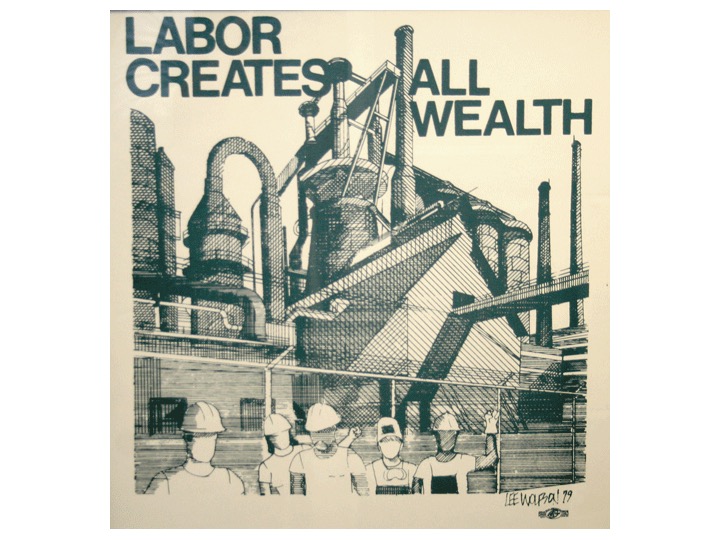

Joseph Beuys’ Wirtschaftswerte (Economic Values, 1980) is made up of shelves displaying decaying groceries from the former German Democratic Republic and paintings created between the birth and death of Karl Marx. When Marx was writing, "value" was a crucial concept not only in the economics of his time but also in an ethics that was shifting from a ‘focus on virtues’ to a ‘focus on values’. The labour theory of value―that the value of a commodity expresses the socially useful labour time that went into its creation―is a central concept in Marx's thought and yet has often been the object of ridicule from bourgeois economists. But, as philosopher George Caffentis argues, "the key question in this matter is: does the transformation of values into prices have explanatory power to help in understanding the structure of capitalism or not?

Joseph Beuys’ Wirtschaftswerte (Economic Values, 1980) is made up of shelves displaying decaying groceries from the former German Democratic Republic and paintings created between the birth and death of Karl Marx. When Marx was writing, "value" was a crucial concept not only in the economics of his time but also in an ethics that was shifting from a ‘focus on virtues’ to a ‘focus on values’. The labour theory of value―that the value of a commodity expresses the socially useful labour time that went into its creation―is a central concept in Marx's thought and yet has often been the object of ridicule from bourgeois economists. But, as philosopher George Caffentis argues, "the key question in this matter is: does the transformation of values into prices have explanatory power to help in understanding the structure of capitalism or not?

(01’12”)

The artist begins talking about Bartleby, the character of a copying clerk from a short story by Herman Melville. She relates how Bartleby takes a position as a scrivener in a Wall Street attorney’s office, initially boosting its productivity, but soon withdrawing from all forms of activity. He stops fulfilling his duties and regularly intones what some commentators describe as his formula-response:

Bartleby soon becomes encrusted in the fabric of the workplace to such an extent that the attorney relocates his entire business. Bartleby is soon removed by the new tenants and is taken to the Tombs prison where he withdraws into death. The artist calls Bartleby a “Zero Worker”, suggesting that he embodies a kind of reversed polarity in the workplace, where the latent copyist, purely by means of ‘non-preference’, ensures that everyone else is at his mercy. She then changes her mind and describes him as a “Working Zero”.

The artist begins talking about Bartleby, the character of a copying clerk from a short story by Herman Melville. She relates how Bartleby takes a position as a scrivener in a Wall Street attorney’s office, initially boosting its productivity, but soon withdrawing from all forms of activity. He stops fulfilling his duties and regularly intones what some commentators describe as his formula-response:

‘I would prefer not to’.

Bartleby soon becomes encrusted in the fabric of the workplace to such an extent that the attorney relocates his entire business. Bartleby is soon removed by the new tenants and is taken to the Tombs prison where he withdraws into death. The artist calls Bartleby a “Zero Worker”, suggesting that he embodies a kind of reversed polarity in the workplace, where the latent copyist, purely by means of ‘non-preference’, ensures that everyone else is at his mercy. She then changes her mind and describes him as a “Working Zero”.

(00’49”)

A number of advocates for a return to institutional critique in art practice have emerged in recent years, including Hito Steyerl, Nina Power and John Douglas Millar. They suggest that such a return would, by necessity, include a critique of art sponsorship by banks and arms traders, and of large corporations that employ casual workers or exploit aspiring artists. Thinking back to Hans Haacke’s Fourth Plinth commision, one wonders if it’s worth holding out hope that it might be a little more contentious than has so far been indicated. Given his 1982 portraits of Thatcher and Reagan―clear protests against nuclear arms and regressive politics―one might hope that his horse’s head will be masked with the face of David Cameron, with an inflatable speech bubble denouncing the poor and praising the ‘return to prosperity’.

(01’10”)

Attempts have been made to give a name to a type of music that finds itself in a seemingly uncategorizable area between composition and improvisation, between Fluxus and the conservatory. These attempts have included ‘new music’, ‘speculative music’, ‘unnamed music’, ‘experimental music’, ‘art-music’, ‘open-form composition’, ‘avant-music’, ‘serial music’ ‘electro-acoustic improvisation’ and so on. The difficulty in defining this ‘post-Cagean’ music [there’s another] is alluded to by Jurg Frey: “[It] is not a label, a style, but a certain way to work and to listen (to music and people, friends, composers) and to try to understand, what the colleagues (and I myself!) are doing... To sit together, to discuss, to play, provoke a response in the style of playing”. Here Frey is talking about Wandelweiser music, but as a collective that attracts participants drawn from various ‘unnamed’ music worlds, the articulation of something like attitude is well-placed.

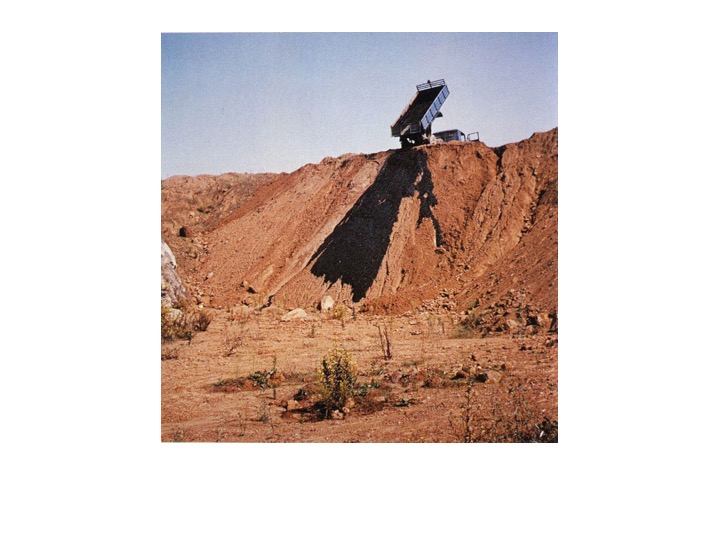

(0’44’’)

In 2005, Sydney Works in Sheffield (commonly known as ‘Matilda’) was opened to artists, grassroots organisations and activists in protest to the contested sale of the building. During the following year, a number of groups converged and set about transforming the mostly derelict space into meeting rooms for local organisations, art studios, a resource centre, cafe and art gallery. The initiative was to reinstate the building as a functional space that provided a valuable service to the local community. The occupation was seen by many as an artwork, wherein the capacity to instigate positive change was considered to be a material with which to make work. The motivation to devise a structure in which to work, and the task of working without a mandate, were catalysts for understanding the scope of artistic practice.

(00’58”)

It is often the case that property developers let spaces to artists in uncertain economic times, yet subsequent gentrification often pushes prices up, only for those same artists to be forced out. Tara Cranswick (Director of V22, a publicly-owned arts organisation that was, until recently, based in South London) makes a succinct argument for the importance of affordable spaces for artists: “Artists contribute enormously to London and the UK economy. Art is the greatest civilising force we have. Artists need space.” But before a feeling of self-righteousness toward myopic city planning takes hold, Cranswick turns her attention to the general public: “Go out and buy some bloody art. Support and become involved in the culture of your time. Forget the big names and the big galleries, support someone interesting and new. You can spend a fortune on a new sofa―I have seen you do it. Keep the old one and buy some art instead.”

www.v22collection.com

It is often the case that property developers let spaces to artists in uncertain economic times, yet subsequent gentrification often pushes prices up, only for those same artists to be forced out. Tara Cranswick (Director of V22, a publicly-owned arts organisation that was, until recently, based in South London) makes a succinct argument for the importance of affordable spaces for artists: “Artists contribute enormously to London and the UK economy. Art is the greatest civilising force we have. Artists need space.” But before a feeling of self-righteousness toward myopic city planning takes hold, Cranswick turns her attention to the general public: “Go out and buy some bloody art. Support and become involved in the culture of your time. Forget the big names and the big galleries, support someone interesting and new. You can spend a fortune on a new sofa―I have seen you do it. Keep the old one and buy some art instead.”

www.v22collection.com

(00’46”)

British composer, James Saunders, has composed a series of scores which use specific locations as sources in the production of text-based compositional instructions. The most recent, Location Composite #6: Waterloo Station, was generated from text supplied by three poets [Amy Cutler, Chris McCabe and Andrew Spragg] who followed the composer’s specific instructions for listening. Speaking about his experience, Andrew Spragg notes how the active listening transformed his sense of a familiar place. The score enacts the demarcation and activation of a period of time, within which material is generated from both the general and specific conditions of a given situation

British composer, James Saunders, has composed a series of scores which use specific locations as sources in the production of text-based compositional instructions. The most recent, Location Composite #6: Waterloo Station, was generated from text supplied by three poets [Amy Cutler, Chris McCabe and Andrew Spragg] who followed the composer’s specific instructions for listening. Speaking about his experience, Andrew Spragg notes how the active listening transformed his sense of a familiar place. The score enacts the demarcation and activation of a period of time, within which material is generated from both the general and specific conditions of a given situation

(00’48”)

In ‘The Serial Attitude’, Mel Bochner observes that the music of American serial composer Milton Babbit “attains a high degree of conceptual coherence, even if it sometimes sounds aimless and fragmentary”. He identifies the grammar of a work as the “permitted combinations of elements belonging to a system” - a definition that could apply equally to improvisation, composition or to the formation of The Set Ensemble. This system can also be adapted to essay and lecture forms. Little is said about its compositional applications but the context that Bochner identifies offers a platform from which to explore potentially parallel ideas in a wider field of ‘grammatical composition’.

In ‘The Serial Attitude’, Mel Bochner observes that the music of American serial composer Milton Babbit “attains a high degree of conceptual coherence, even if it sometimes sounds aimless and fragmentary”. He identifies the grammar of a work as the “permitted combinations of elements belonging to a system” - a definition that could apply equally to improvisation, composition or to the formation of The Set Ensemble. This system can also be adapted to essay and lecture forms. Little is said about its compositional applications but the context that Bochner identifies offers a platform from which to explore potentially parallel ideas in a wider field of ‘grammatical composition’.

(00’44”)

For the second incarnation of ‘Writing as Occupation’, a circular space is occupied between the hours of 9am and 5pm, with writers clocking in to account for all time spent writing and not writing. The circular space is located in a former prison. Incumbent writers do not live in the space, nor do they attempt to barricade themselves in, yet their occupation will be explored as a daily task open to public view and interaction. Writing stations will involve technologies ranging from pen and paper, manual and electric typewriters, to computers linked up to printers.

For the second incarnation of ‘Writing as Occupation’, a circular space is occupied between the hours of 9am and 5pm, with writers clocking in to account for all time spent writing and not writing. The circular space is located in a former prison. Incumbent writers do not live in the space, nor do they attempt to barricade themselves in, yet their occupation will be explored as a daily task open to public view and interaction. Writing stations will involve technologies ranging from pen and paper, manual and electric typewriters, to computers linked up to printers.

(00’46”)

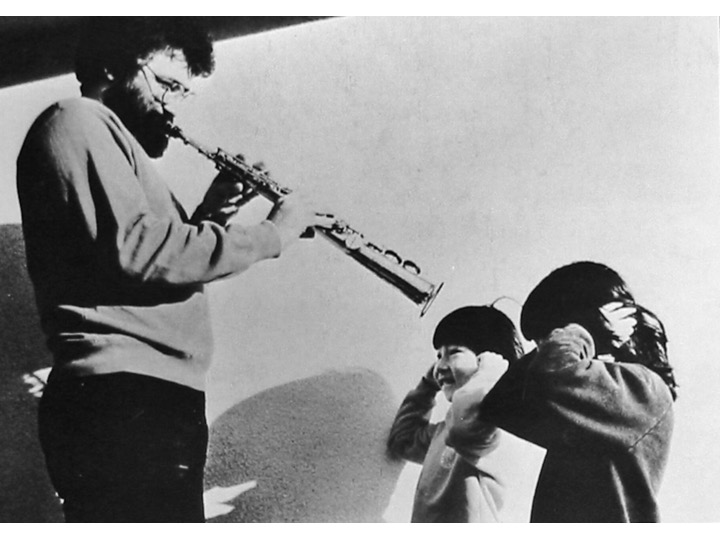

Improvising saxophonist Evan Parker says in Ian Carr's book Music Outside (published 1973, when Parker was about 29), "My wife has always been my sponsor. She works, so when I'm not earning anything she carries us through… she's a teacher. [...] She knows that I actually work very hard… a lot harder than if I just took a job in an office and just went in there and drowsed and looked at my watch and made a few notes on a piece of paper… the civil service type of job… I work much harder than that. I don't stop… [you know,] the hours aren't nine to five… it's work the whole time, but then it's also leisure the whole time. It's a different life-style… you can't divorce work from play."

Improvising saxophonist Evan Parker says in Ian Carr's book Music Outside (published 1973, when Parker was about 29), "My wife has always been my sponsor. She works, so when I'm not earning anything she carries us through… she's a teacher. [...] She knows that I actually work very hard… a lot harder than if I just took a job in an office and just went in there and drowsed and looked at my watch and made a few notes on a piece of paper… the civil service type of job… I work much harder than that. I don't stop… [you know,] the hours aren't nine to five… it's work the whole time, but then it's also leisure the whole time. It's a different life-style… you can't divorce work from play."

(00’48”)

Jurg Frey’s observation that the Wandelweiser collective embodies a “certain way to work and to listen”, echoes Mel Bochner’s identification of seriality as ‘attitude’, a “method not a style”, one that is concerned with how “order of a specific type is manifest”. Bochner’s text, ‘The Serial Attitude’, written in 1967, presents a number of areas where ideas concerning contemporary art, music, linguistics and mathematics are found to correspond. The essay, first published in Artforum, offers a glossary that includes definitions of ‘Set’, ‘Series’, ‘Progression’, ‘Grammar’ and ‘Simultaneity’, all of which loosely correspond to this ‘unnamed’ music.

Bochner, M. (1967) ‘The Serial Attitude’ in Art Forum, 6:4, December 1967, pp. 28-33

Bochner, M. (1967) ‘The Serial Attitude’ in Art Forum, 6:4, December 1967, pp. 28-33

(00’50”)

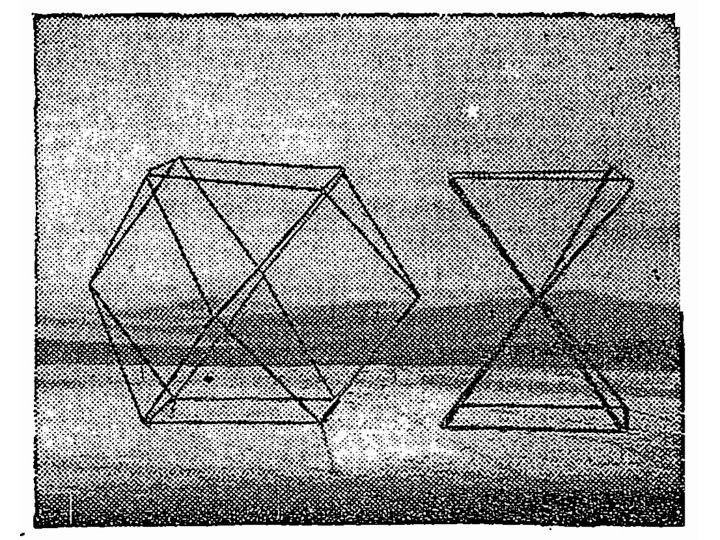

The Void Belonging to Created Things is an installation developed during a residency in Brussels in 2012. Split between two rooms, the installation consists of objects found on-site: a roll of paper, a stack of chipboard, sound-proofing foam, a radiator bracket, etc. The positioning of these materials aims to recover the formal sculptural quality of the objects and to create a relationship between the materials and the space. The work in the first room is informed by material atomism, whilst the second room exhibits composites formed from found objects. Throughout the space, repetitions and parallels are set up between objects and occurrences in the architecture: echoes and reflections of colour, material and form.

The Void Belonging to Created Things is an installation developed during a residency in Brussels in 2012. Split between two rooms, the installation consists of objects found on-site: a roll of paper, a stack of chipboard, sound-proofing foam, a radiator bracket, etc. The positioning of these materials aims to recover the formal sculptural quality of the objects and to create a relationship between the materials and the space. The work in the first room is informed by material atomism, whilst the second room exhibits composites formed from found objects. Throughout the space, repetitions and parallels are set up between objects and occurrences in the architecture: echoes and reflections of colour, material and form.

(00’46”)

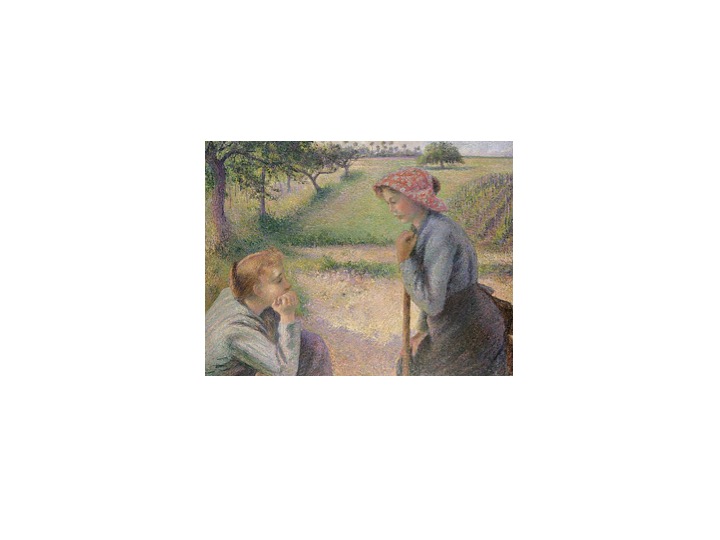

In Pissarro’s painting, Two Young Peasant Women, it has been suggested that what is laid out under the painter’s brush is a reclaimed moment of idleness within the field of work. In contrast to the industrial worker, the farmhands’ moment-apart is something they control for themselves. The stolen instant in the shade, if it is that, must be qualitatively different to that granted through the inbuilt compensations of employment. The two figures are depicted in full possession of their powers.

Camille Pissarro - Two Young Peasant Women (1892) oil on canvas, 89 x 165cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In Pissarro’s painting, Two Young Peasant Women, it has been suggested that what is laid out under the painter’s brush is a reclaimed moment of idleness within the field of work. In contrast to the industrial worker, the farmhands’ moment-apart is something they control for themselves. The stolen instant in the shade, if it is that, must be qualitatively different to that granted through the inbuilt compensations of employment. The two figures are depicted in full possession of their powers.

Camille Pissarro - Two Young Peasant Women (1892) oil on canvas, 89 x 165cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

(01’02”)

A number of arguments for idleness have arisen, with an understanding that it would be more profitable for the human condition to rethink the balance between work and non-work. Profit was originally understood as progress, benefit or advancement. Bertrand Russell argued that humanity would profit from a four-hour working day; Buckminster Fuller that we would all profit from returning to education and concentrating on what it was we were interested in before we were told we had to earn a living. Rethinking idleness as a form of profit enables questions to be asked about what ‘progress’ is, what it means to ‘make profit’ and to whose benefit?

(01’22”)

If words take on the form of objects then they are objects around which one can navigate. In 1969, Marcel Broodthaers redacted Stephane Mallarmé’s Un coup de des jamais n'abolira le hazard [A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance] replacing the text of the poem with black lines corresponding to its layout and typography. Broodthaers emphasised the poem’s spatial distributions, using structure as his material. The page is therefore presented simply as a space for the articulation of relationships between content and form, with spaces between phrases as equally weighted as the words themselves. The vacancies within the poem are central to its reception. An example of how space can be used to articulate a concern is exemplified by Mallarmé and then further underlined by Broodthaers.

If words take on the form of objects then they are objects around which one can navigate. In 1969, Marcel Broodthaers redacted Stephane Mallarmé’s Un coup de des jamais n'abolira le hazard [A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance] replacing the text of the poem with black lines corresponding to its layout and typography. Broodthaers emphasised the poem’s spatial distributions, using structure as his material. The page is therefore presented simply as a space for the articulation of relationships between content and form, with spaces between phrases as equally weighted as the words themselves. The vacancies within the poem are central to its reception. An example of how space can be used to articulate a concern is exemplified by Mallarmé and then further underlined by Broodthaers.

(01’04”)

The artist informs me of her contact with the Artist Placement Group, an organisation which acknowledged the marginalised position of the artist and sought to improve the situation. Through negotiation and agreement, the artist was told that she had been assigned a placement within a specific industry, where she would become involved in the day-to-day work of an organisation, be paid a salary equal to that of other employees, whilst occupying a role with sufficient autonomy to act on an open brief. She accepted the placement immediately and handed in her resignation at the bank. Her new role at the bank marks a significant improvement in her working conditions.

The artist informs me of her contact with the Artist Placement Group, an organisation which acknowledged the marginalised position of the artist and sought to improve the situation. Through negotiation and agreement, the artist was told that she had been assigned a placement within a specific industry, where she would become involved in the day-to-day work of an organisation, be paid a salary equal to that of other employees, whilst occupying a role with sufficient autonomy to act on an open brief. She accepted the placement immediately and handed in her resignation at the bank. Her new role at the bank marks a significant improvement in her working conditions.

(00’59”)

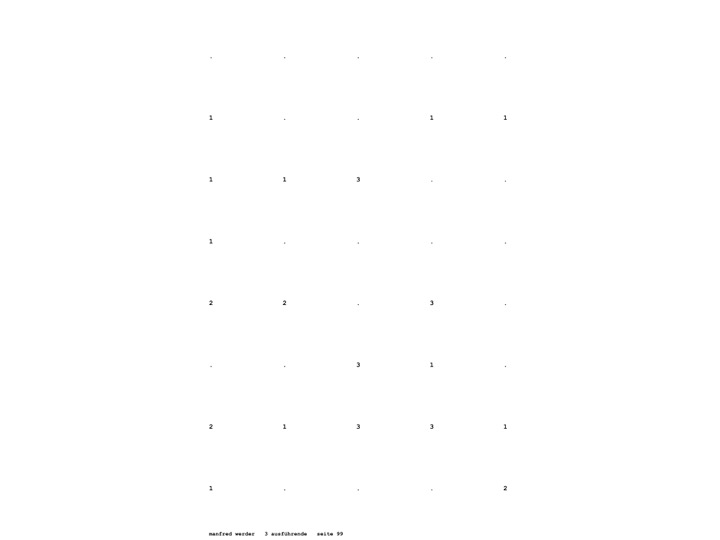

Composer Manfred Werder has written a number of scores of enormous length (4000 hours or so), but with the stipulation that the pieces are played in fragments. Every performance of one of these pieces begins at the point in the score where the last performance left off. When―or if―the last page of any of these pieces is reached, that piece will never be performed again. Thus we have compositions that are performed often, in many parts of the world, and yet, strictly speaking, will only ever be performed once.

Composer Manfred Werder has written a number of scores of enormous length (4000 hours or so), but with the stipulation that the pieces are played in fragments. Every performance of one of these pieces begins at the point in the score where the last performance left off. When―or if―the last page of any of these pieces is reached, that piece will never be performed again. Thus we have compositions that are performed often, in many parts of the world, and yet, strictly speaking, will only ever be performed once.

(00’46”)

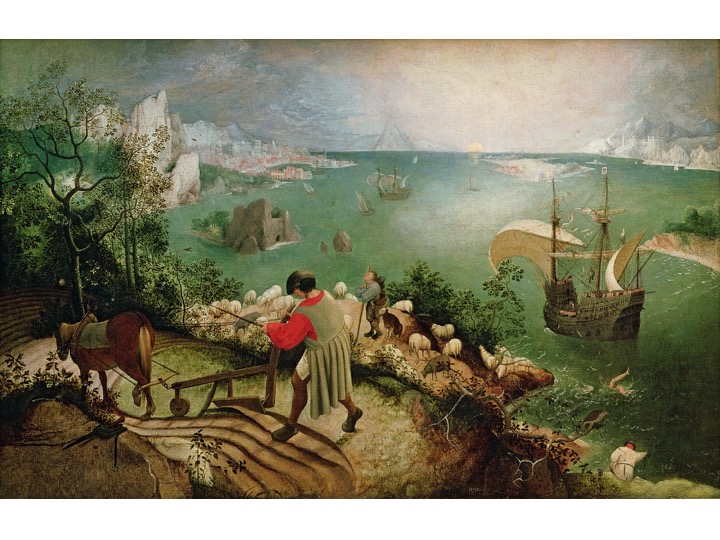

When the ‘freefall’ of the precarious worker reaches its conclusion―when Icarus is swallowed by the waters―perhaps the established patterns of work, production and consumption, each a distinct sphere of activity marked out as private property, will simply continue, indifferent. A figure falls, unnoticed, and the farmer continues to plough.

When the ‘freefall’ of the precarious worker reaches its conclusion―when Icarus is swallowed by the waters―perhaps the established patterns of work, production and consumption, each a distinct sphere of activity marked out as private property, will simply continue, indifferent. A figure falls, unnoticed, and the farmer continues to plough.

(01’31”)

But a more positive image, perhaps, suggests that within the strictures of working life, there are revealed possibilities for new ways of thinking about creative production. John Berger speaks of how Millet’s ambition to “introduce previously unpainted experience” into his work led to him setting himself impossible tasks. Berger describes an image of a couple working in the fields, the man hoeing the earth, the woman dropping seed potatoes. With the potatoes frozen in mid-air, Millet captures an instant more suited to the cinema than to painting. As Berger says: the instant might “be filmable, but is scarcely paintable.” But leaving aside its intrusion on to the territory of cinema, what Millet may actually achieve is rather an image of the inherent creative possibilities within established fields of work.

Berger, J. (1980) ‘Millet and the Peasant’ in About Looking. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, 76-85

But a more positive image, perhaps, suggests that within the strictures of working life, there are revealed possibilities for new ways of thinking about creative production. John Berger speaks of how Millet’s ambition to “introduce previously unpainted experience” into his work led to him setting himself impossible tasks. Berger describes an image of a couple working in the fields, the man hoeing the earth, the woman dropping seed potatoes. With the potatoes frozen in mid-air, Millet captures an instant more suited to the cinema than to painting. As Berger says: the instant might “be filmable, but is scarcely paintable.” But leaving aside its intrusion on to the territory of cinema, what Millet may actually achieve is rather an image of the inherent creative possibilities within established fields of work.

Berger, J. (1980) ‘Millet and the Peasant’ in About Looking. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, 76-85

‘37.5 Fragments Toward an Occupation of Time’ was composed by Sarah Hughes, Dominic Lash and David Stent and originally presented as part of ‘ZERO HOURS - What Artists Do’, Transmission Lecture Series, Sheffield, 2014.