12 Angry Diagrams

ATKINSON / BAYER / BURKES /

FLOYD-STEINBERG

HILBERT / JARVIS / JUDICE / NINKE

REANO / SCOLORQ / SIERRA / STUCKI

![]()

FLOYD-STEINBERG

HILBERT / JARVIS / JUDICE / NINKE

REANO / SCOLORQ / SIERRA / STUCKI

01

A mistake has been made. The juror identified as Bayer is in fact Stucki. The imposter leans slightly to the right. The visage is of one confused. Amongst the twelve this could only be Stucki. Bayer, as you will remember, is an altogether harder creature. More intelligent. We found him with a brace of automatic weapons. He was able to show the correct permits. Consequently we have been unable to remove the side arms from his possession. The relevant orders have now been sought. But in the meantime he has pulled some strings. It is impractical for us to act. Currently he is installed at Pohlmann’s campaign headquarters. We think this is a diversionary tactic. Our man keeps an eye on him. Members of the team are mapping the peripheries of his operation. They are watching those branches with which he does not appear to be in regular contact. We believe he will make his move soon. When he does it will be from a place like this. His network is convoluted, extensive. We are short of resources. It falls to me to request some extra help. In the meantime I will look for the image of Bayer. We have one in our possession. I’ll fax it to you. I suggest you update your records.

M

02

Stucki and Bayer are always interchangeable. They take it upon themselves to engage in such switches, each one impersonating the other, and now they are in danger of fooling you. You must maintain vigilance. I will relay the same directive to Pohlmann – we’re all in unfamiliar territory. If my thoughts were to be drawn, I would suggest that by far the most interesting of the twelve is Scolorq. I watch his sunken features and heavy brow occasionally flare into light – an impression no doubt influenced by my knowledge of him as the so-called theoretical pyromaniac. His influence on the group will prove fascinating. On the feed I have been given to monitor he is often alone, sitting quietly inside Room A or in one of the ballrooms, the enforced heat not seeming to affect him at all. He wears eyeglasses now, which I have to admit surprised me. I seem unable to dissociate him from his old ways, hearing his former patterns of speech in my head, his relentlessly evasive equivocations. He was always a favourite of mine. I used to enjoy the ceaseless distribution of his pamphlets and the stories of the cells of writers he had under his tutelage. In any case, you should observe Scolorq’s way of moving through the Hotel and watch how he interacts. You might see the workings in his eyes or catch glimpses of a family history riddled with holes. Of course our records are always incomplete but remember – for now you are my eyes and ears on the ground.

O

03

M – On O’s request, I am sending you a panorama – three shots taken from the lounge window and cropped as accurately as has been possible. This is Scolorq’s view, roughly speaking, while he works in his notebook. We wonder if the simulated vantage helps you to predict what he has written? It is O’s belief that such a view might have impressed on it the thoughts of one who has looked up unconsciously whilst working. Shortly I will be collecting data from the building’s other apertures.

On a different note, and in confidence, I draw your attention to his final remark: ‘you are my eyes and ears on the ground.’ The turn of phrase is ordinary enough but it strikes me as unusual. I find it inflected on account of my other recent assignment. O has instructed me to make a study of the grounds, to photograph portions of the paths. His request was no more explicit than that. Naturally, since I cannot ask him directly, I have been looking for clues to help me understand his reasoning. Now I can’t help but imagine the double meaning in his remark to be a piece in the jigsaw. Any thoughts you have on this matter would be appreciated.

P

04

These types of request are not uncommon. You should fulfil them to the best of your ability but try to maintain a critical distance. Wider vistas will open out for us in time. More pressing are the rumours percolating about the various clusters and pacts being established amongst the twelve. As I don’t have direct access you must try to keep me up to date – these infiltrations may prove useful going forward. The thing is, to give a specific example of the relationships we’re concerned about, Reano will not be far from Scolorq for any length of time; Reano – that pale, wizened figure has been designated as ‘scribe’ in the past. In fact he has been transcribing various pronouncements with increasing frequency, his employ not limited to Scolorq either, although that powerful figure has dominated the more recent requests, more so since the scar tissue in Scolorq’s hands has started to contract. At least this is the information we’ve been given. As to what Scolorq is dictating, everybody’s guessing at this point. The only thing we’re convinced of is that it all amounts to a collection of theoretical or philosophical pronouncements, building up into some kind of vast treatise for all we know. I guess it would form a comprehensive system or at least be figured along such lines – Scolorq was never afraid of ambition. And so, of course, Reano will shadow him wherever he goes, equipment at the ready. Practical details will no doubt be at the behest of Scolorq too – he’ll growl at Reano the Albino (if indeed he is still called that), telling him in no uncertain terms which tool should be used to mark out the latest instalment. Actually, in the past I’ve seen them both in the gardens, scratching away in the gravel or in the flowerbeds. As I write this it dawns on me that this could be part of the reasoning behind your task. Posterity is important here, so it could be that you are responsible (albeit unconsciously) for maintaining records of some description… and that we are surrounded by near invisible ‘texts’ inscribed throughout the grounds. If it all weren’t so serious I’d be tempted to laugh. May I ask if a system has been established for cycling through the pathways and apertures? Is photography the only medium you will use for this work? I’ll be intrigued to follow reports of your duties, back there in the thick of it.

05

“I’ve seen them both in the gardens scratching away in the gravel”

The observation does expose a possible origin for the photographic survey instruction. It is possible that the visual record is being made not for the purposes of decrypting messages. The latter begins to look like a diversion. Are the surveyor and his assistant being directed simply to mimic the gestures of the two mentioned? It would explain why the images are never properly employed. Where is O when the survey takes place? There are many high windows. The camera operator’s bowing posture and his gripping of the device might be a way by which O restages the appearance of the two for his own surreptitious viewing. The question presents itself: could O’s directives be carried out as effectively – perhaps more effectively - without the recording device? He has been determined to shield us from full knowledge of the work; his instructions come in mysterious, truncated form. I am tempted to suggest that only now is the full extent of his control becoming apparent. Like a chess player he has been planning several moves ahead, making sacrifices for the grand scheme. If this is so, everything changes. His intentions can be second-guessed. Our overview will swallow his, extend it. We will draw him into our service instead; we will do so without his knowledge.

Regarding the cycling and your wondering whether “a system has been established for cycling through the pathways and apertures”, the survey takes place once in the day around midday while the twelve are occupied in the canteen. Ten-minute intervals are observed between the serving of one and the serving of the next. Consequently there are seldom more than four eating together at any one time. But they are in the habit of queuing in the corridor (in a double file) and they rest in the lounge a while after, which provides a reasonable period.

The surveyor is accompanied by a trainee (bag-carrier) who waits by the main entrance while the bicycle is retrieved from the shed, after which the circuits can commence. The bag-carrier may follow on foot, but it is advised that he should not jog while in charge of equipment. The initial cycling survey is conducted in loops. These should be wide, taking in the whole grounds and undertaken without pauses. When the survey is complete, the bicycle can be left on its stand by the entrance or returned to the shed, but it should be hidden from view before any of the twelve appear (they have been informed that there is no bicycle). For the second phase, the surveyor and trainee precede on foot, focusing now on locations at which a disturbance can be seen to have taken place. At certain times of the year the study must look also at configurations of fallen leaves, but the procedure is the same in any event.

06

From time to time I’ve had cause to complain about the efficacy of these survey cycles and what I consider futile attempts to monitor the twelve from the visible effects they have on their surroundings. I’ve been privy to other directives, of course, some of them unofficial, some of them yet to be approved – each of them more absurd or extreme than the last. I’ve been obliged to attend training courses, to pick through leaflets and manuals, to follow the prescribed points of a language that is becoming increasingly unfamiliar to me. I don’t wish to say that I have lost faith entirely or that I intend to strike up resistance. In fact I don’t even mean to suggest there’s nothing in this philosophy, if that’s what it is – this theoretical concern for the twelve and the manner in which they’re processed, and whereby we become indebted. We continue to get tangible results. Even I cannot deny this. I have my doubts but I’m no conspiracy theorist. You could say I’m a sceptic but I shall always keep this to myself. I will let you in on something, however, something I haven’t told anyone before. Once I was lined up to be a trainee myself, when I was quite young – which seems a long time ago now – I considered myself something of an expert in the circuit procedure (how the contours have changed!), was learning how to operate the recording equipment and harboured dreams of one day taking control of the bicycle. I cannot recall when that adolescent aspiration faded or quite how I came to be employed so near, and yet so far, from this once-desired role. I’m taking you into my confidence here, I’m putting my trust in you. I confess… I’ve made mention of the bicycle to one of the twelve but quite deliberately – cruelly – chose Floyd-Steinberg as my confessor. Floyd-Steinberg. That maniacal creature, the raving mute… the man whose eyes we have to shut with pennies every night. In a quiet corner I told him all about my childhood association with the grounds, the bicycle rounds, my growing scepticism. I was distraught when I thought I noticed a tremor of recognition float across his face but, since that day, nothing has happened. Nothing has happened.

07

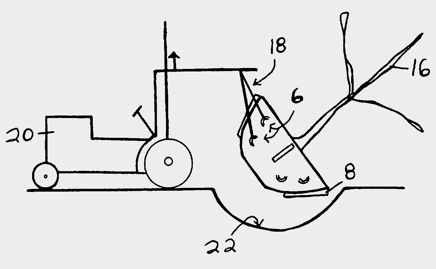

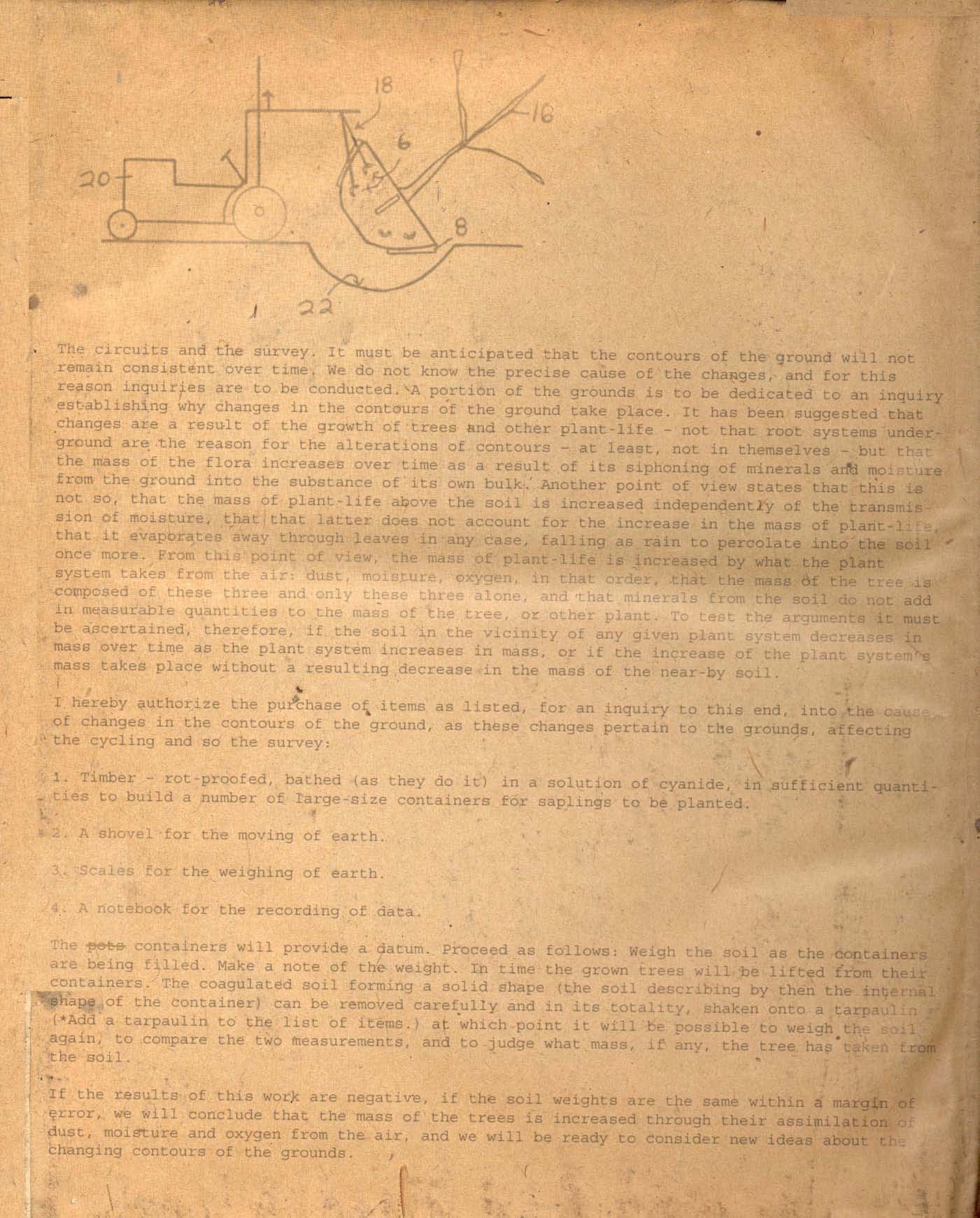

The circuits and the survey

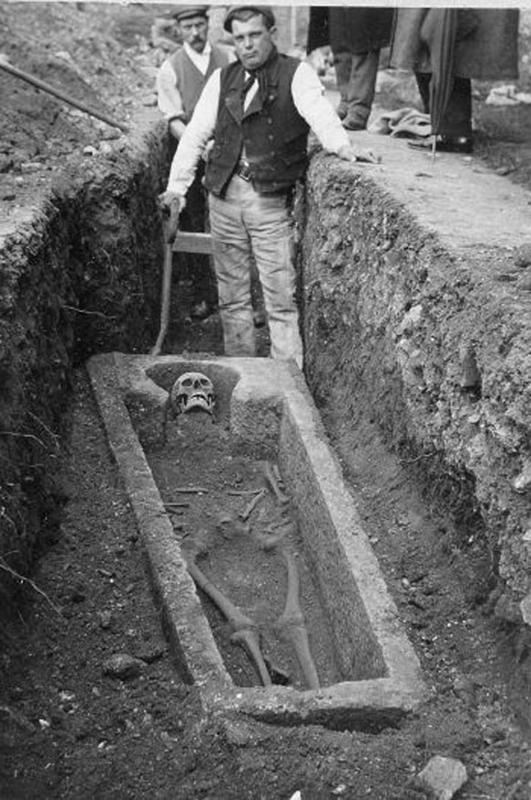

It must be anticipated that the contours of the ground will not remain consistent over time. We do not know the precise cause of the changes and for this reason inquiries are to be conducted. Arrangements will be made, a portion of the grounds dedicated to an inquiry establishing why changes in the contours of the ground take place. It has been suggested that changes are a result of the growth of trees and other plant-life – not that root systems underground are the sole reason for the changes in contours but that the mass of the plant life increases over time as a result of its siphoning of minerals and moisture from the ground into the substance of its own bulk. Another point of view states that this is not so, that the mass of plant life above the soil is increased independently of the transmission of minerals and moisture; that the latter does not account for the increase in the mass of plant life; that moisture evaporates away through leaves in any case, falling as rain to percolate into the soil once more. From this point of view the mass of plant life is increased by what the plant system takes from the air: dust, moisture, oxygen; that the mass of the plant-life is composed of these three only, and that minerals from the soil do not add in measurable quantities to the mass of the plant life. To test the arguments it must be ascertained whether the soil in the vicinity of any given plant system decreases in mass over time as the plant system increases in mass, or if the increasing of the plant system’s mass takes place without a resulting decrease in the mass of the nearby soil.

I hereby authorize the purchase of items as listed, for an inquiry, into the cause of changes in the contours of the ground as these changes pertain to the grounds, affecting the cycling and the survey:

- Timber – rot-proofed; bathed as they do it in a solution of cyanide, in sufficient quantities to build a number of large-sized containers for saplings.

- A shovel for the moving of earth.

- Scales for the weighing of earth.

- A notebook.

The containers will provide a datum. Proceed as follows:

Weigh the soil as the containers are being filled. Make a note of the weight. In time the grown plants or trees will be lifted from their containers. The coagulated soil forming a solid shape (the soil describing by then the internal shape of the containers) can be removed carefully and in its totality and shaken onto a tarpaulin (*add a tarpaulin to the list of items). At this point it will be possible to weigh the soil again, to compare the two measurements, and to judge what mass if any the plant has taken from the soil. If the results of this work are negative – if the soil weights are the same within a margin of error – we will conclude that the mass of the plant is increased through their assimilation of dust, moisture and oxygen from the air and we will be ready to consider new ideas about the changing contours of the grounds.

08.

I took the inventory this morning, as per the latest directive, watching the twelve make their way along the dull corridor to the canteen. The figures squeaked and popped: Bayer, Floyd-Steinberg, Jarvis and Judice, Ninke, Stucki, Burkes, Scolorq, Sierra, Atkinson, Hilbert and Reano. As they disappeared from view I emerged and passed across the floor to the vaulted window at the mid-point of the walkway. Looking beyond the grounds I could make out the first divisions of machinery casting their loops around the final periphery markers – it will not be long until this building is properly isolated by their tourniquet. Only later did I find out that at this moment a conflagration occurred in the canteen – discussions about governance having turned suddenly violent. Initially it was assumed that Sierra had been attacked – I thought this myself when the captured images were replayed at Pohlmann’s HQ – given that he was shielded from view by figures crowding around him. Subsequent observations however, indicated that Sierra had been attempting to attack himself in some way – most likely with the improvised system of straps and cords that was later found abandoned in one of the stairwells – and the crowd had endeavoured to ‘assist’ him. Sierra’s makeshift contraption consisted of a bodice fashioned from leather belts, intricately laced with loops of piano wire that could be tightened individually or in one forceful, clenching movement. Given the relatively superficial wounds observed on Sierra’s body, we can be sure that only a few of these mechanisms were put into effect. As part of the ongoing investigation into the incident I am scheduled to visit the ballroom this morning in order to examine the piano. If the current theory is correct the absent ‘notes’ – where the hammer mechanism will emit an awkward ‘cluck’ when a key corresponding to a missing wire is struck – will constitute an encoded notation from which concrete evidence can be gathered as to the ongoing deliberations of the twelve.

09

After being told of trouble that has taken place elsewhere, it is odd to think back on what one was doing while in ignorance of events. They call it the morning room, that space the twelve favour as their gathering point, before, one by one and in alphabetical order, they file off to receive their daily meal. But in fact the room is rarely used before midday, and it is hardly a room in the normal sense. It was a passage before one of the many ‘audits of accommodation’ reclassified it. With some extravagant adjustments it has been widened, a storage cupboard in the eaves having been sacrificed to open the space for better social function. But one becomes aware of a certain unease, the origin of which can be traced to the wainscoting. This interior’s embellishments and furnishings manifest contempt.

I followed, lagging behind but drawn in their wake nonetheless. Their mumbling conversation was almost audible; I was conscious that I should not be found listening. The last of them – the artless Stucki – made his way to the canteen. As I stood in the silence I tried to feel their absence as a tangible thing, as something recent. The framed picture by the alcove gave itself to my proper consideration for the first time. (I know it intimately but cannot recall one single occasion of having studied it.) It is a page cut from a picture book slipped behind the glass. No care has been taken even to secure the sheet in place, so it is the pressure of its backing board that stops the picture from slipping further behind the yellowing mount. It struck me that this one item in the morning room’s inventory is of a different kind. The picture testifies to a certain security that someone has established for the benefit of another, the nurturing care that an adult feels for one under his charge. And yet there is no minor admitted into this place. It appears that amongst the twelve in a previous era some such relationship surely existed.

10

I found myself thinking of relationships amongst the current twelve. By now we had been monitoring them closely for a long period of time, but as I examined the faded image I was struck by the potential extent of our ignorance when it comes to the delicacies of interaction between these men; how their various exchanges of reliance, security and tenderness may have been expressed unseen all along. I exhaled the exasperated realisation that we would not even know how to recognise such expressions. For too long we had been directed by a stream of notices drawing our attention to superficial alliances between individuals – relations that could well have been described for us in such a way that we then invent our observations of them. For too long we had been manipulated by endless warnings of ‘alien’ collusions, hostile conglomerations of knowledge. We were told we were not in a position to understand. The emptiness of our targeted observations became clear. Yet what moved me most of all, what seemed to solidify in my throat, was the possibility that any form of nurturing relationship amongst the twelve, however inchoate or faltering it would have to be, was truly absent – a thought that filled me with great pity and sadness. At that moment the brutal, clinical nature of our mediated relationships with the jurors began to overwhelm me. I looked again at the image that had stirred these thoughts and noticed, this time consciously, delicate annotations made with a black ballpoint pen in an unsteady hand. Over three small circles of exposed paper pulp, where the sheen of colour had been stripped as if by a drop of caustic, a series of crosses had been inscribed. Set at different rotations, these marks plotted a shallow arc increasing in size from right to left as they moved toward the edge of the paper. It was possible that the marks signified kisses or projectiles travelling through the sky – those types of specifics didn’t interest me. What the naïve crosses evidenced – and it seemed certain that, if they were not a child’s annotations there was a childlike quality embedded in them – was a laying claim to the image. It betrayed a sense of security and being at ease with the depicted world such that it could be safely overwritten, re-inscribed or claimed with an ‘X’. The presented world was possessed to the degree that it could be altered.

11

Jarvis has an unnatural smile twisting the corners of his mouth. This inspires mistrust, but only in a first encounter. There is no malign intent. His expression is a symptom. It reveals a long-established stress for which Jarvis’s face has, over time, become the arena. The work that the mouth does could be shifted elsewhere, to another part of the body. But at his time of life the effort would require resources no longer easily coordinated.

Jarvis is a Gentleman’s hairdresser. It would be going too far to call him an expert in matters of appearance, but he is required every day to give advice along these lines and does so with a certain proficiency. He is a stealthy commentator on the image appearing in the mirror, the sheet-wrapped client, as he stands at the rear with comb and scissors in hand. Jarvis is no different from others of his profession, others of his generation. His proficiency is no indication of personal stakes nor investment beyond what’s required of him. It is his job. His comments on matters of hairdressing have to be no more than mild-mannered interjections to everyday conversation.

If the relaxed mode of his expertise borders on complacency it is a surprise that Jarvis should have made such a questionable decision concerning his own appearance. Most of his acquaintances would tell you that Jarvis has dyed his hair black for longer than they can remember. Few know his natural colour. But then, his friends and customers are the kind who do not spend time thinking about such things. They are without exception of the same generation as Jarvis. Open attention to such matters is discouraged. The curiosity that he should colour his hair is not unrelated to the singularity of his expression. There is some trouble that he is inclined to hide. It is of his past but emerges in the present, shows itself in every facet of his restricted existence. Jarvis himself would not put it this way – in fact he would have nothing to say on the matter. To disguise every trace of the trouble would demand resources he does not possess but to restrict the trouble to the arena of his expression, this he can do. Even coming before his profession this is his daily work, his exhaustion.

12

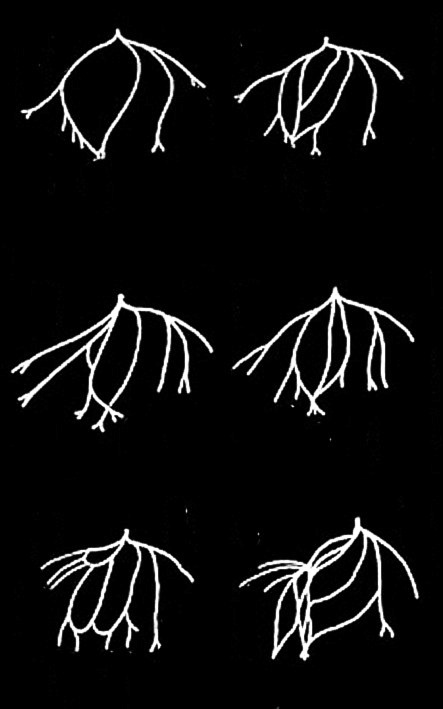

Another perspective was given by Judice, the taciturn figure so often found following directly behind the hairdresser down the corridors of the Hotel. His account was notable not least for its exhaustive detail, but also for the unexpected passion with which it was delivered. Although the instalments of this story were procured unofficially, in different locations, something of their substance has filtered through into other branches and departments, in some cases taking root. Judice was always a notorious fantasist yet his account has been given some credence by the confirmed association with Jarvis outside the confines of the Hotel. It has even been verified through photographic evidence that Jarvis cut Judice’s hair – although never to his satisfaction. A broad summary of the account relates that, for Judice, a specific pathological cause lay behind Jarvis’s smirk: an adolescent onset of facial palsy. Adamant about the veracity of his claims, Judice suggested that the condition had started with a disturbance to the third (or oculomotor) nerve, which caused Jarvis’ right eye to slip down and outward, apparently accompanied by extravagant hallucinations of colour and migraine headaches caused by extreme double-vision. Soon this localised paralysis began to disperse across one side of the face. As his facial muscles drooped away from the skull Jarvis’s expressions became halved – Judice’s comment was that he was either “asleep or awake” depending upon the direction from which he was approached. Yet there were further complications to Jarvis’s story. An initial diagnosis of Bell’s palsy was both confirmed and made more complicated when the other side of the face also became paralysed – the immobility spreading unchecked like a contagion. Soon after that, however, the paralysis eased then became intermittent and variable – to the degree that physicians eventually began to question whether Jarvis had any conscious “control” over his “facility”. According to Judice, the doctors were convinced that Jarvis could disengage his face at will. They suspected he used a “switch” to freely inhabit a blank suspended mode of expression – perhaps when situations were not to his liking. But as Judice pointed out, this resulted in the uncoupled mode, far from divorcing him from any necessity of “recognisable response”, becoming just another expression. From the beginning of his account Judice claimed that the onset of the palsy was triggered by an “event” Jarvis had witnessed and soon began to make similar claims about the moment when control over the palsy began to lessen. Another “image”, again not explained or expanded upon by Judice in any way, severed Jarvis’ ability to engage with the symptoms of his ailment. His face gradually regained its poise and resumed its involuntary betrayals of interior feeling – Jarvis could no longer hide. It was then, as the nerves began to recover their autonomy, that the awkward grin settled at the edge of Jarvis’ mouth – a kink that would never again leave his lips. Our observations, perhaps influenced by the etymological associations of his name, suggest that Judice sat in judgment of Jarvis in many ways. Something of this attitude could be read in his own puckered countenance – the face of a compulsive, artistic fabricator. On this point it’s worth noting that, when he was placed in front of the blackboard set up for him in the empty ballroom so he could illustrate his accounts, Judice demonstrated an idea by drawing what he described as “articulations of the facial nerve rendered as patterns of rainfall tilted over plate glass.”

13

Judice, overweight, hair like straw, is sitting by his flip-chart, a mug of coffee in one hand, the other drumming the floor with the thick end of a billiard pole. This time next year he will be dead, lost when his light aircraft comes down in open fields outside Denver. He raises his voice, tries to capture an audience from amongst the few others who still remain collecting their things. They are folding the tables, returning them to an adjoining room to be stowed against the wall. The chairs can be stacked behind the curtain at the far end of the hall. His vocal skills were never developed, Judice explains. Otherwise he would have had a career performing the songs he has written over the years. Some of his numbers have achieved success in collections recorded by others. But as a consequence of his lack of interest in performing, he goes on, the body of work is not as well-known as it should be. It is dispersed too widely, diluted by the different styles of the singers who have interpreted his work (taken liberties more often than not). Still, a well-informed core of enthusiasts can speak of his oeuvre, even if they do so only amongst themselves. Of course Judice was never really a dedicated musician either, neither pianist nor guitar player. He strums a little, but to have the kind of mind he does, quick at distilling events down to their essence, able to shuffle the notes of a tune well enough while scribbling words, this is the song-writer’s gift. It can be honed over years. He dares point out that he has devoted time to the honing. If they knew the lengths of his effort they would hail him – not just for his commitment but for the reticence that has put this labour out of common view. Atkinson nods his agreement. It takes Judice a moment to grasp the feeling of irritation provoked by the response of his one attentive listener. Atkinson’s nodding is automatic. Judice casts his words a little further, trying to hook Ninke, who is busy with his belongings.

“Ah’ve long been on the open road and sleepin' in a bag, from dirty words and muddy cells ma coat’s become a rag…”

Ninke packs his shoes into polythene along with his jumper and a few books. Hilbert arrives holding a paper parcel. The two exchange remarks in low voices. Judice can’t make out what is being said. Perhaps a discussion is taking place about how best to divide up the weight of items between sacks that may not be strong enough.

14

What would have previously evolved into Atkinson’s critique lingered as a barely remembered instinct – one that had been neglected for so long that its potential extrapolations couldn’t have been accounted for. Far from attending to the compositional structures of the music or the facility with which it was being performed – eyes closed under blond mop, right-hand rhythm led by a mirrored Django mitt – Atkinson was instead cornered by the combinatory effect it was having on his hearing. Instead of the familiar swirl of tinnitus and pealing interference he had been forced to live with for the last three decades, clear peaks of sound began to emerge, waving and flaring in his ears. He smiled coyly to himself, wary of being made to feel a fool and still unsure what was happening to him. The critic is always patient, he told himself. He didn’t want to move, think or do anything that would disturb the natural course of these events. He would allow the music to chip away at his faculties. Even as his hearing continued to sharpen he suspected there were crossed wires somewhere – as if a pain signal were somehow being reformatted or that he was being persuaded by an intrusion of imbalance into thinking his hearing had returned. Soon his desperation to prolong the effect got the better of him. Atkinson gently started to reposition his head, cycling his chin through various elevations as if nodding assent. A new sensation in his ear disturbed him momentarily – a tight vibration on the drum loosening and separating until it was cleanly isolated into discrete packets of rhythm. Soon this uncomfortable pinch faded and the room dilated suddenly. Atkinson could make out a pair of voices behind him. He turned his head, scraping the collar of his starched shirt against the skin of his throat. Two of the foreigners he found he could now understand. They were speaking English.

“Ignore him,” said Hilbert, “open it.” Between them they were unpeeling a small packet, as if neither of them trusted the other to complete the task.

“Ex libris. What’s ex libris? A former book?” exclaimed Ninke.

Atkinson chose this moment to let out a startling roar, the first time in decades that he had done so. He felt familiar vibrations passing through his jawbone but was particularly moved by the way his cry rattled elegantly through frequencies he thought he had lost forever. The jarheads were all standing by their beds, shocked, as the guitar crashed noisily onto the carpet and tipped into a pile of storage boxes. The group had been packing their things – but who knew if it was a question of leaving the building, the room, or whether it was just another reinvention of the inventory? Atkinson had made his decision long before the music had released the bung from his ears, but now found that he was even more determined. He would not place any of his possessions inside those slimy polythene bags sitting in a pile at his feet.

15

Palaeontologists reconstruct the soundscape of an ancient time through their study of bone fossils. Tubular cavities in the skull of Charonosaurus are understood to have worked as resonance chambers, nature’s organ pipes emerging 70 million years before Homo sapiens and his musical tools. The Charonosaurus skull cavities gave the creature’s call a deafening volume. Today’s loudest animal is the Howler Monkey. The Howler’s volume too is achieved through an unusual vocal mechanism. It differs from its simian contemporary in having a hyoid or throat bone, which is cup-shaped at one end with a slender arm at the other. A hook on the arm’s extremity works as a pivot, slotting into a corresponding depression in the vertebrae, which gives the bone several degrees of radial movement. The resonating hyoid provides a natural amplifier for the larynx, accounting for a call that is in fact less a ‘howl’ and more a piercing squawk.

In her early anthropological work with South American aborigines, Ruby Gabraw studied the relationship between these indigenous people and the Howler Monkey. She documented the role of tribeswomen in their communication with the animal, noting that the so-called ‘monkey callers’ had developed a technique for casting the human voice into the same register of volume, this being achieved by inserting a carved piece of Agave wood into the throat. With practice the carefully fashioned resonator could be kept in place permanently, although the tribal monkey-caller was then restricted to eating mashed and diluted food. Always keen to test scientific method Gabraw conducted her own experiments, having some limited success with a modified spoon which she was able to extract from her throat by means of a cord tied through a hole in its handle. In the introduction to her pamphlet How the Howling Happens, Gabraw narrates that her hosts name her ‘K’rkopiwich’ or ‘mouth-tail’ in reference to the cord which she kept tied to a brooch on her lapel, thus ensuring that if she should swallow the device it would be quickly retrievable.

In the years following its publication, How the Howling Happens has found an unexpected readership amongst travelling performers in Europe, its text and illustrations becoming the basis for a vocal practice that some consider more at home in the freak show than under the auspices of music. Unlike its earlier manifestation the European squawk is practised exclusively by men, with volume being prized above quality. More recently the vocal tradition’s evolution has been the subject of theory that attempts to distil its constant elements, and to identify aspects of the practice that transform in migration from one continent to another, indexing social norms as they do so.

16

“So, at that point, Hilbert walked over to Atkinson, who was now lying quiet… supine in the middle of the floor. The whole room was silent. I saw him examining Atkinson’s mouth but evidently he observed no trace of thread or anything that could be attached to modified spoons or swallowed tree fragments… I should explain that by this time I had read through part of the introductory section of the text Hilbert had just given me, which seemed weirdly apposite to what happened – a copy of How the Howling Happens which, according to the stamp on the inside cover, belonged to someone else… perhaps someone in the group – I couldn’t make out the monogram [maybe SCQ?] Anyway, at that moment I wondered if it related to how Atkinson produced such a startling noise. In fact I think that the possibility of Atkinson emitting his roar using nothing other than his own faculties, without any of the modification techniques described in the text, was evident from the expression of hesitant admiration that came across Hilbert’s face – I say hesitant… he held back, I think, as there was no way for him to convey such a sentiment without disturbing the man who lay unmoving at his feet. Perhaps there were other reasons. But anyway, this was a passing moment… nothing other than a weird coincidence. All it would tell us, I would guess, is that Hilbert often read the material in his possession. As Hilbert then turned to rejoin me, I quickly closed the pamphlet and pretended to examine the author’s photograph on the back. What we shouldn’t lose sight of is the fact that the gift being given to me was, at that point, a significant step. Initially I was sure that it confirmed the growing trust between myself and Hilbert – one that suggested we weren’t far away from discovering more about his communication network. I knew that Hilbert was in possession of a large number of pamphlets, the majority kept on his person, others distributed throughout the spaces of the Hotel. Of course he was never the author behind the material but only a distributor – I would testify that he played no part in preparing leaflets and in fact possessed little in the way of creative imagination. You could say that he was a salesman, fond of the process of exchange, of bartering – especially when it was conducted according to assumed models of the black market, no matter how false or contrived these models were. It wasn’t as if any money was changing hands. You all know this. Anyway, what I had been working on for weeks was immediately deflated when I noticed the stamp – it was a strange woodcut design bordered by a near-circle, maybe a dodecagon or something, with an isolated castle inside it if I remember rightly. Perhaps others can identify it. It was clear at that point that if Hilbert wasn’t in fact on to me and playing games, he was at least fobbing me off with a superfluous copy of this Gabraw publication - a copy not taken from his own stores but a duplicate he had fashioned or stolen from another individual. He was throwing me off. I had tried to goad him with a dumb comment about the stamp but this effort was foiled, first by Atkinson’s caterwaul, then by our unforeseen transfer. Typical. I couldn’t risk bringing it up again without jeopardising my cover.”

17

The brothers stand by their beds waiting for instructions. One fidgets, the other is still – so still as to appear hypnotised, his gaze prodding mindlessly at the elastic space of the hall. Neither of them will have the presence of mind to admit it but they miss their mother. The unspoken sadness of their adult lives is nothing more complicated. Just as she provided security for them under a strong arch of intolerance, so their gestures are to this day those of the guilty. On odd occasions, peeking through the crack between the doors, a witness can see the pair squatting on their camp beds. They are crew-cut. Their thighs are sturdy, the fabric of identical khaki shorts drawn tightly into crevices describing contours that would be better hidden. When they were young one brother would have invited the other onto the bed, or one would have consented to let the other join him in order to go through the cards. Then, as now, the cards needed to be checked. The checking is carried out daily. But the broadening of their bones (which began in adolescence and has persisted into middle age) makes it unwise for them now to add their two masses on any one piece of furniture. When Stucki sits there is a worrying creak of canvas, of steel against timber.

In the quiet hour after dinner, unaware of being watched, their gestures will become those of children again. At such times, even if the phrases are meaningless to others listening in, meaning can be deciphered through style and a private world exposed. A demand made by the elder brother, offence taken by the younger, objection voiced, counter-objection returned, compromise mooted then agreed, fraternity restated: all this occurs in a moment of barely connected syllables and flicks of the body.

In many ways Bayer and Stucki have grown to resemble each other less over the years. But the issue of identification polarises their associates. For some the difference is primary, similarity becoming apparent only later as a sudden and astounding inflection. Others when confronted with a vision of the two throw their arms up in submission, exclaim that they can find no way of distinguishing between the brothers, employ strategic vagueness, address the two as one.

A closer look at the contents of their tins shows the dog-eared cuttings to have a theme. Eras are spanned. You might not see right away but Bayer and Stucki’s exchanges draw it out. ‘That one’s you; this one’s me.’

Hilbert arrives with instructions. The tins are closed, packed into the hole. Bayer stoops to lace his boots. No announcement has been made but the members situated throughout the premises emerge now as one dispersed body in preparation for departure.

18

Although there is no signal, no obvious leader, the group bleeds out of the room in a fluid movement. Personal effects have been piled up on a trolley – boxes and bags carefully arranged on the flat bed of plywood reinforced by a bracelet of steel. The whole arrangement has been roped to Floyd-Steinberg even though he pulls it quite naturally using its articulated handle. When held vertically this handle reaches his collarbone. The trolley runs smoothly, without sound, but occasionally pivots over carpet kinks because of its four fully rotating casters. Floyd-Steinberg takes up the rear of the forlorn procession as it winds its way along the main corridor. Every individual takes note of surrounding changes in their own way – some notice the renewed silence, others the removal of furniture; some seek out apertures in order to take one last look at what’s left of the gardens. The corridor opens out on to the stairwell landing, apparently the one remaining section of the building still papered with original floral wall coverings. A section of ceiling is punctured with a grid of drill holes, evidence of an incomplete transfer of cartoon drawings onto its stucco surface. The group funnels across the landing and down the curve of the stone stairwell, the bowl of the main reception area slung beneath in chocolate-coloured shadow. Lagging slightly, Floyd-Steinberg pulls the laden trolley to the top of the stairs, slowing as some form of recognition of his predicament comes to him. He manages to formulate a required change in elevation as he sees the rest of the group pooling in the foyer like docile animals. He watches them through gaps in the marble banister, looking down into darkness yet disturbed by the feeling that it will always be him down there, being exhibited inside the sunken enclosure. No one is looking for him or waiting. He continues walking ahead, descending two steps before stopping to look back at the trolley looming over him. He is not panicked but is overcome with despair. He lets the handle fall from his hand and watches it come to rest like a crooked limb pointing downstairs. He walks back up to the landing and past the trolley. At the limit of the rope he gently radiates out in an arc until he reaches the deep green wall. Staring at its pattern of knotted leaves and stems, gazing through constellations of sunflower and chrysanthemum, he starts to move his hand towards the paper. It begins with the index finger alone but before long the thumb mirrors it. It looks as though he is about to pinch off stars – deadheading an escape from this world. Soon the middle finger extends into a spot adjacent to the index, followed by the ring finger, which pairs up awkwardly with the thumb. Two sets of limbs line up as if for battle, the pinky retracted into the palm like a tail. Floyd-Steinberg then proceeds to walk his quadruped hand up the wall, across a floral universe, with complete disregard for elevation, direction or what lies behind the paper.

19

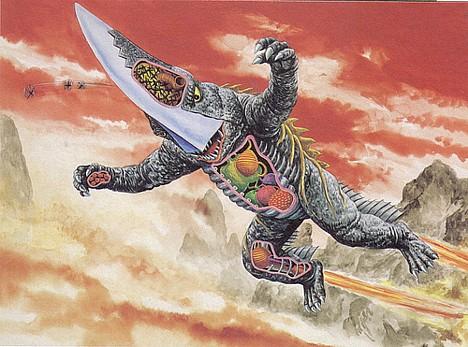

Their pod had made a hard landing. The surface was less dense than readings indicated, low weather systems interfering with the orbiter’s preparatory soundings. But with a little force from inside the Bluntbeaks had aided the pod’s four petals to drop into open formation, after which it was easy enough to manoeuvre the Pedacle Rover into an altered position so that it might negotiate the unscheduled obstacle of the pod’s lower lip, tilted as it was by a minor collapse in the outer skin. F-Berg had led his team through this move effectively, growling his order, singling out one or two habitual insubordinates for especially rough treatment, making their punishment a lesson to the rest. The resistance they showed was superficial, with no transmission between it and any resolution of will. The low-cast intellect was irredeemably shallow, incapable of tactical organisation. In this way even the less predictable of them could be trusted with a weapon and a Pedacle commander could be confident that no mutiny would take place. F-Berg had learned to read the signs of forthcoming stubbornness. He would bark his rebukes and watch the trouble subside, the dearth of expression across the low-casts’ leathery features provoking him to imagine their collapse of resolve in more overtly physical terms: a barrier penetrated by the crowbar of his authority.

Strapped into his cockpit, with the low-casts patrolling the Pedacle’s flanks on either side, he was in control. The rover lurched hesitantly, automated risk assessment guiding each footfall, finding gaps in the vegetation, plotting dangerous surface debris. The colour and contours made this terrain look like salt-flats but the plant life told a different story. Perhaps they had landed on the dried bed of an ancient river. If so, at one time a substantial volume of water must have flowed. There were no riverbank features within view, only the perfect level of a sparkling plateau towards hills that might be close or far - it was difficult to tell. The same weather that had given them trouble on landing could be seen now as an unusual phenomenon. This was a world ordered by extreme atmospheric cycles. The profusion of brightly-coloured, crystalline vegetation springing from the crazed surface must be recent. If they had arrived here even two days earlier perhaps they would have been journeying across a different kind of land. Without the carpet of intricate organic forms to draw their attention, their eyes would have settled instead on the horizon. And time too would have cast itself forward into that placid distance, the rhythmical breathing of the Pedacle’s pneumatics giving them the beat of a current moment, impinging on their consciousness only intermittently. Yet in the midst of such a miracle of exuberant life, with their gazes captured by immediate surroundings, time was first a vibrant and multiform present. And now it was the vehicle’s mechanical plodding that sent their thoughts into that other time of horizons, towards the thin strip of light and the two suns that made tunnels for their journey.

20

Progress is sluggish and demands patience, yet the tilted arrangement of lights in the distance – a sliver of heat-haze enclosed by bulbs – slowly sharpens. In one way or another the texture of this section of horizon pervades every occupying thought, as if its profile serves as a motif of the expedition:

O_______________________________O

Although any trace of curvature in the arrangement is no longer apparent, the whole procedure is weighed down by the time already invested; expectation hangs off the mission like moisture. Even if it is sunken and almost out of sight, there is a visible destination – an emanation that seems increasingly irresistible. Soon enough the terrain starts to de-saturate. All trace of greenery is lost. Everything smoothes out; firm shadows decrease significantly, bar those cast by craters stirred up by surfactants and horsehairs. The approach is streaky, flaked, possibly bled white by the encroaching radiation. But instead of the expected heat the opposite sensation starts to descend. The possibility that this zone is littoral takes hold. It seems that even in the presence of overpowering light, moisture is not far away. The atmosphere is heavy with it as if storm chains are about to split like purses. At this range the beam can be clearly seen rising in an asymmetrical rhombus, sharp-edged as if still insisting it is as hot as a solar flare. Nonetheless it is a chill forbidding expanse that unfurls, all heat having long since been discharged. Without warning a series of glossy steps descend and the earth falls away – it vanishes under a sheet of transparent resin, un-textured, glass-flat. There is no choice but to ride the momentum – the Pedacle Rover is unmoored, skating uncontrollably over the expanse and quickly losing all bearings. Soon the sheen constitutes all of the available world; everything is warped by it, made distant, inanimate and specious. Rich colours just passed through are now forgotten, set apart. Floral forms are irreversibly matted, as if behind aspic, and magnified to terrible proportions. Immediately, as if in automatic response, the Pedacle’s fins retract and clench just ahead of a brutal pneumatic movement – a lateral jolt that forces a net drawn on the sheen surface to crumble in on itself. A storm of debris, including the Pedacle, punctures into the vacuum and travels on without sound. Accelerated by the pressures of this new expanse the trajectory of the Rover betrays an attachment to a mass it had otherwise persuaded to follow obediently behind – the force of its drag quickly switching to downward propulsion. Thus commandeered, the fist quickly opens again into a hand, fanning out as if to greet the wet concrete it now rushes towards. Drops of glass have already dusted the dark ground surrounding the geometric lines of the parking bay (the joined-dot constellation of a charlatan astrologer) but the hand does not join them. A sudden stop, savagely doubling up the Pedacle’s trailing mass, marks the extension of the rope. At its other end, the trolley is wedged in the shattered window, steadily tickled by a man-sized pendulum. Every now and then a few paper packets drip down onto the tarmac.

Written by Neil Chapman and David Stent. First published in Chapman’s Protowork as Art's Expanded Writing Practice, PhD Thesis, University of Reading, 2011.