On Music

Text We'd Like to Write

The Church of St Anne & St Agnes sits at an elbow turn amongst high rises, a short walk from St. Paul’s underground. A space designed in proportionate clarity by Wren, the building is approached through a triangular garden that passes through small portico before breaking into a spacious, yet curiously hunched main volume, banded by austerely arched windows, a series of pastel columns, a dubious Britannica crest and a corner organ stacked up like a cake to the right of the pews. Regrettably, this was the first Music We’d Like to Hear concerts that I’d been to, but the line up of pieces curated by the composer Tim Parkinson suggested that this would be a good occasion to start. The evening began with Vincenzo Galilei’s Contrapunti (1584), a two-voiced work carefully performed by Angharad Davies and Sara Hubrich on violins. Delicate melodic phrases interwove and coalesced with both precision and occasional slurring, and had the effect of somehow opening up the space, or even awakening the ears after the relentless city noise and chaotic activity that had been waded through up until that point in the day. It might seem a vaguely dismissive thing to say about a piece of music, but it did offer something of a palliative, a stirring method by which one might clean a ‘receptive surface’ (in what? attention span; consciousness?) such that whatever followed (even in the extending act of listening to the Galilei piece itself) could be dealt with according to renewed ‘availabilities’, an arrested state of listening. I guess this is meant less as a comment about Contrapunti than as an acknowledgment of Parkinson’s adroit choice of opening with it.

It was quickly followed by Parkinson himself, joined by James Saunders – both credited with playing ‘any sound-producing means’, which in this case at least included bells and pipes, sticks on overturned gongs, bows pulled across bowl lips, tin whistles and melodicas – performing Michael Parson’s 1978 piece Pentachordal Melody. The structure of the piece appeared to involve the revolving recurrence of five pitches in a semi-improvised (or unidentifiably ordered) sequence. An information sheet picked up at the door provided a sequence of numbers in a small grid, which was to be used by the players in order to determine both the “order of pitches and the number of notes in each phrase.” The music was steady, intermittent, with various alignments and overlays beginning to build up a ‘vertical’ texture on top of the expansive horizons of silence and deliberate points of sound. At times it seemed that the piece risked becoming too mechanical, or its back and forth exchanges between players too predictable, but then this was dispersed as the instrumentation changed or odd coincidences caused the piece to reel away, simultaneously exposing the tension that had been built up almost surreptitiously. The texture of imminent collapse, perhaps punctured by a taxi chirrup just beyond the church walls, became established almost without noticing, no doubt partly due to the calm confidence of the performers and their full inhabitation of the time needed to move from one phase of the work to the next. At the end of the piece, Parsons, who was in the audience, rose to take a round of applause – an acknowledgment he graciously redirected onto the players in front of him through a semi-physical gesture of transference that both resembled some sort of game involving a ball being passed on with minimum contact, and the piece of music he had written into sound.

Davies and Hubrich then returned to the stage to perform Chiyoko Szlavnics’ Interior Landscape, a piece that demanded unusual fingerings and sustained glissandi, such that the composer apparently had to work with the players to find the best techniques for generate exactly what was intended. Pitches were grouped in odd clusters – a view of the left hand would present a taut cradle, one digit of which would suddenly slip, either down to another stop or even hopping onto another string, moving from one sustained pressure point to another, as if a specific ‘gearing’ were being shifted one cog at a time (one petal from a bloom), each movement both a gain and a loss not wholly unanticipated as the overall sound from both players is buffeted by the other pitches, beating intervals, or revealed as a transparent counter to what was resting on top of it. One hand kept racing under the other, as if pouring sand were falling from one palm to the next, each rising slide braced for slippage. A clock mechanism dotted with sponges, still nodes and escaping strands. The last piece before the interval, performed again by Parkinson Saunders, was For John (Material), a Christian Woolf piece dating from 2008, dedicated to John Cage. The information sheets suggested that the composer considered the work an “anarchic canon” in which where specific material common to both performers is distributed independently. This approach, thematically threaded through the two-fold pieces throughout the evening, allowed for continuous possibilities for alignment and discordance, as partial recognitions and echoes between each performer came to the surface. The piece resembled that of Michael Parsons yet seemed a more committed extension of a similar premise. The performance was sparser, lengthier, and was somehow more effective in establishing it’s architectonic, as it were, through the volume of the church.

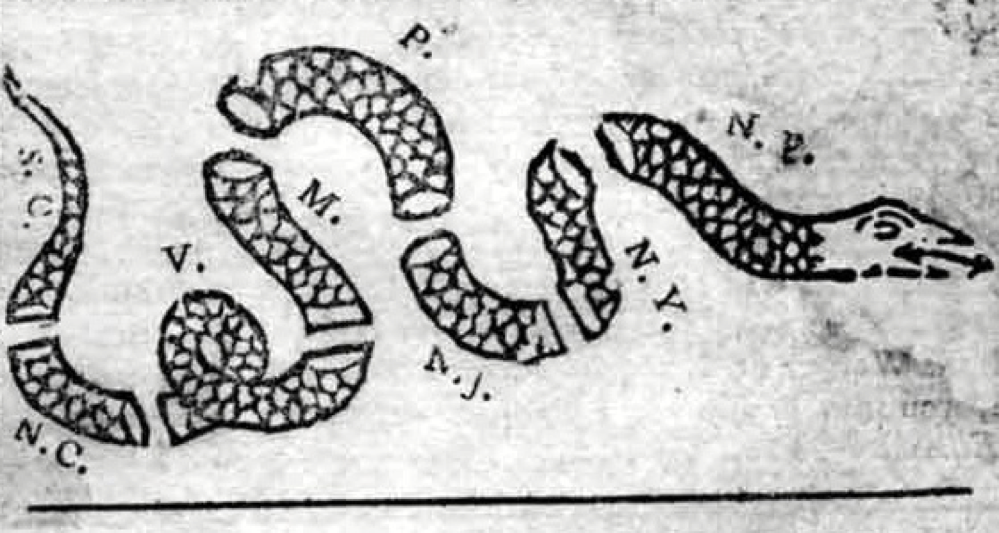

After a brief interval, the second half of the concert was taken up by a performance of Jürg Frey’s Ohne Titel (Zwei Violinen). In a more substantial note Frey, a composer associated with the Wandelweiser Group, suggested that the piece makes a two-fold address to the perception of time, suggesting that it can be encountered either as a ‘path’ or an ‘expanse’, a claim that seemed to make sense when considering the proximity between the two performers in a number of senses, repeated actions, mirrored physical gestures, and musical repetitions and ruptures. The piece accommodated both relentlessly repeated events and abrupt changes that could not really be anticipated. Davies and Hubrich would often matched each other with incredible precision (Davies appearing to assume a lead with silent count-ins, barely perceptible nods and facial indicators that could well suggest only my misreading of the situation), yet never managed to disappear into the same space as it were – never defeating pesky physical laws. The two violin ‘lines’, in laying so closely side by side, either copied or in symmetry, revealed any deviation, grain or slip (in the clay) and allowed to be unobtrusively emphasised, underlined in contingent delicacy and in its unequivocal occurrence. I was as if the smallest of differential increments could in effect become enlarged (makes me think of those deserts and water spouts in Francis Bacon, the eruptions of hidden oceanic pressures, an unbounded universe poking out of a dirty sink…). Again, the duration of the piece focused the attention on these details, these flaking borderlines, mixing everything together with general fatigue and the lure of exposed breathing patterns. At times the head became suddenly exposed as a rudder hinged on the neck, or rather unstably embedded in the upper chest, starting to swing a little from tiredness, or as a result of a certain lilt or lean in the textures being mapped out for the ears. Not a rudder for steering in the sense of firmly establishing direction or any stable route to be followed (i.e. not as part of a learning mechanism) but rather a fluid and unpredictable (probe) head… the image comes of a particular kind of plastic toy snakes that I used to play with as a child, which was broken up into many segments articulated on pins such that a side-winding movement could be made, even if the snake was held at a single gripping point. When holding one rear segment, the snake’s body could be made to sweep from side to side in such a way that its motion could not really be tracked – they were too slow to provoke and too fast to react to… obviously there were only certain movements that could be made, certain planes into which the joints could be prodded, yet the ‘overall’ line would wave like a supple spine, coherent and unaffected. So what, then? Being at the head of such a snake, sat on the prow to listen – where is this point in relation to ‘path’ and ‘expanse’, as if you could get one without the other…? – the stability that afforded access to these unforeseen movements of the leading edge became buried in the composition, hidden elsewhere, perhaps in the snake-belly of the structural instrumentation, or the specific components involved in the this performance in that space… all such things combined…as a band of images for the most part, potentially sprung from a coiled position on a hard pew, a passing imagining of a St. Sebastian ekphratically(?) wrought by Flann O’Brien, where assassinating arrows taper down to near-invisible threads passing through the saint like music; backdrops of Yves Tanguy that had been stripped of those tiny objects, details that the young Dalí would rip off, just leaving smoky expanses; the sound of a jet being heard as a definite handful of pitches, striking its tangent to London as its grip of tones was steadily relinquished and stripped away – a sonic leaflet campaign – at a moment when Ohne Titel stepped clusters of five repeated strokes seamlessly down into four, as if the music were subject to a crystalline fragmentation that couldn’t possibly be tracked and could never, despite its beauty, be relaxed into completely.

City of Freedom

As the first performer of the 2010 Freedom of the City Festival at London’s Conway Hall, the American trumpeter Peter Evans’ swirling reveille announced proceedings with unabashed drama and poise. A swirling, metallic loop of sound was introduced without preface, immediately swilling around the space as if the listener had always been in the middle of it. Tones began peeling off from one another, reverberating through the curves and lintels of the hall, just as they furred and buzzed the knot of the inner ear. Evans’ technique being so impressive, the level of drama that he embodied and played up to seemed of interest, especially in comparison with the performer who would take to the stage later in the festival, Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith. Performing in a trio with the fine drummers Steve Noble and Louis Moholo-Moholo, Smith characterised another kind of dramatic presence altogether, tapped into a powerful charisma in a way independent of the qualities of the music being produced. And let’s be clear – the music produced by both Evans and the trumpet and drums trio was remarkable. Having immediately embarked on his crackling loop of sound, squeezed and swerved by the swallows of circular breathing, Evans marshalled his trumpet like a high-pressure hose – occasionally (and quite ‘dramatically’) letting his lips breaking their seal and flare out a blast of air, as if some release were necessary for the ongoing movement to continue. This relentless stream of modulated forms was soon broken, however, and with an inevitable loss of the elasticated tension that had been slowly constructed, the performance moving into a series of tight note clusters, raced through and repeated in a way reminiscent of clawhammer guitar picking. The overlapping patterns were occasionally interrupted – when Evans carefully switched to piccolo trumpet – and there was a sensation that these interruptions were not engaged with as musical material as much as they might’ve been, with the effect that, when they did occur, they were more like strange, unwelcome intrusions – necessary gaps (as if to ‘change reels’ or some other mundane, technical task) that nevertheless could have been exploited as a sonic territory on its own terms. It may be that this is more difficult when playing solo (even though there is less chance of silence in groups), and that the articulation between silence and sound get relegated behind other more pressing concerns. Yet Evans clearly has a keen sense of structure and has the ability to constantly revise the trajectory of his material in a very effective way. His use of amplification was perfectly judged, bringing the volume up just short of a distracting distortion in order to deliver low noises of such physical power that they induced visions of an amplified grain silo which was slowly filling up around the audience. The tiniest movements of the mouth were routed through the amp and projected over the space as if magnified – which in turn added strange folds to the texture of the sound, occasionally suggesting the hidden presence of choral voices in the wings, providing a staggered harmonic accompaniment. Later, when Evans played in a trio with Evan Parker and Okkyung Lee, this strange ventriloquism was such that it was as if another valve or opening had been commandeered at the musicians’ backs. While there was less of the extended techniques in the playing of Wadada Leo Smith (although he could fray a beam of sound for fun), such was the drama and poise of his performance with Noble and Moholo, he managed to transport the simplest sequence of tones into a form of significance and gravitas. The rhythmic washes provided by these two drummers set up Smith’s playing in a compelling way – condensed snatches of rhythmic grooves wouldn’t come full-blooded, but instead emerged augmented or half-eaten, always at a slant, levered into the territories of the other musicians like laden trays. Across these sliding pulses – most often syncopated and retracted by Noble, slurred then simplified by Moholo – Smith occasionally cut through with tender, even melancholy phrases, dotted with nervous pitching. A lengthy passage came about where even the musicians seemed somewhat stunned by the charged space they had conjured and became oddly reticent, before being chanted back into movement. Smith, having squatted out of sight for a few moments, rose vertically into the frame and proposed a series of phrases, as Noble dragged wet digits around the drum skins, slipping a bulbous squeal underneath them. The drama of the set was calmly unravelled, without bombast, in a way that made it seem like it had ended that night of the festival, even though a number of groups had yet to take the stage. For me, however, the subtle nature of the drama addressed here was evidence when Smith attached the mute, slipping the range of his sound right into the heart of what had already been established, as if part of a vanishing trick, and the delicacy of his attack began to suggest “something to make the stars go to sleep” – a phrase intoned to introduce the trio’s closing piece.